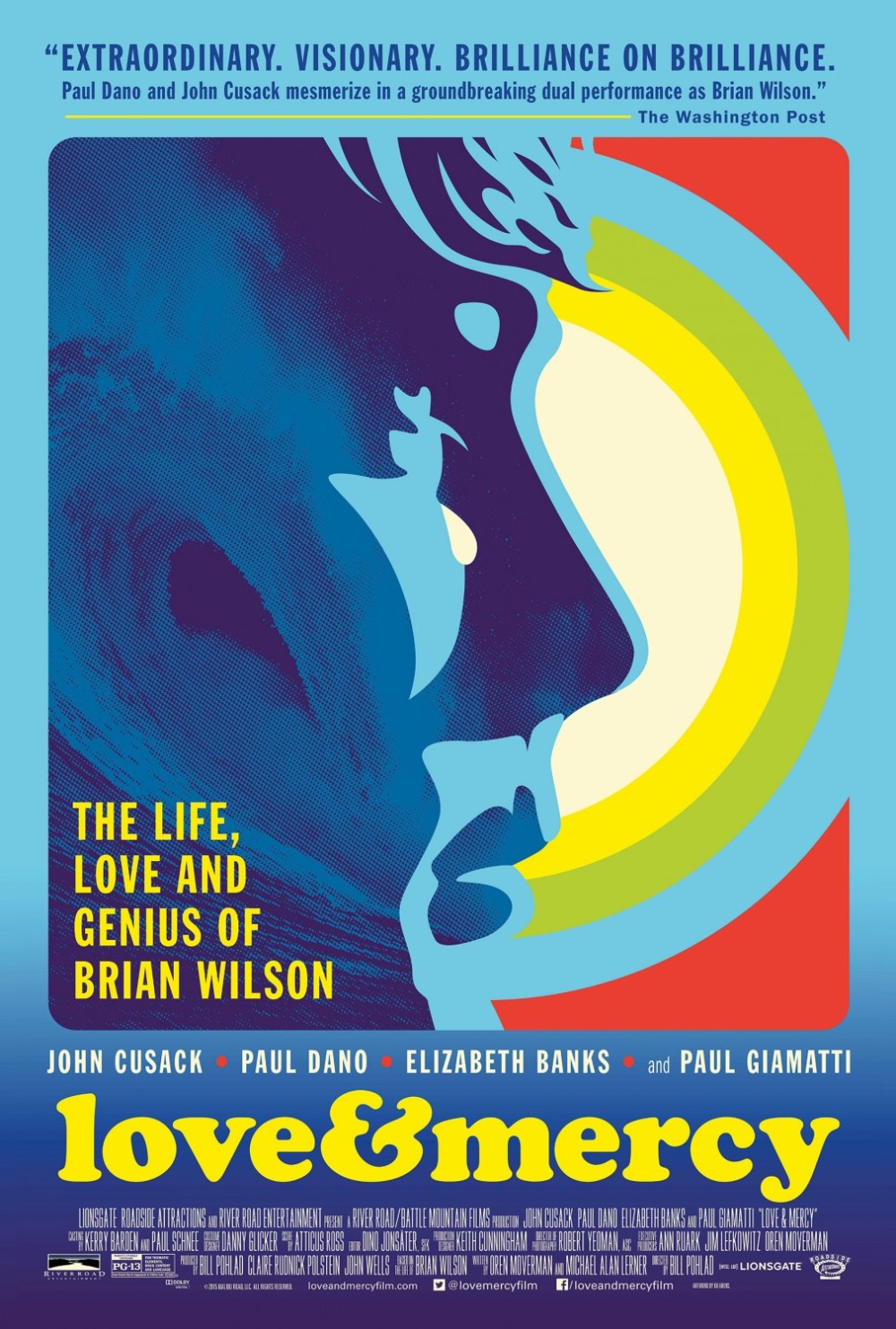

So I’m back home and back reviewing movies, and I’ve got quite a bit of catching up to do. There are a number of reviews I’d like to get out in the next two weeks, and originally this was to be part of a triple review with Tomorrowland and The 100-Year-Old Man Who Climbed Out the Window and Disappeared. But this film is good enough to have its own article, and indeed, it’s one of the nicest surprises of the first half of 2015: a musical biopic that just might stand on its own cinematic legs in the years to come. As with many such films, it highlights a superior lead performance(s), but Love & Mercy has more to it than that. It’s a hell of a film in a lot of ways, and even if it probably won’t make a tenth of what Jurassic World made in its first weekend, it’s by far the better film.

See it before it’s gone.

TW: Mental illness, psychological abuse

Love & Mercy tells the tale of Beach Boy Brian Wilson using two intercut timelines:

- In the 1960s, Brian (Paul Dano) and the Boys have achieved great success with their early pop tunes, but Brian has bigger things in mind, namely the dauntingly experimental Smile, the composition of which begins to overwhelm him at the same time it alienates his bandmates. But as Brian’s mental health begins to deteriorate, his ability to reconcile his ideals with the pressures placed him by others crumbles.

- In the 1980s, Brian (John Cusack) has achieved some semblance of stability under the control of Dr. Eugene Landy (Paul Giamatti), who demands total control over Brian’s life and lashes out at any sign of defiance from anyone. When Brian begins a relationship with Cadillac dealer Melinda Ledbetter (Elizabeth Banks), she realizes that he must break free of Landy, but this is no easy task.

The dual casting of Dano and Cusack probably raised more than a few eyebrows; could these two very different actors (who don’t greatly resemble each other) craft a coherent performance between them? They do, and it’s for their work that Love & Mercy will be remembered in the years to come.

Dano is an actor I’ve had mixed feelings about before (I found his work in Looper especially grating), but the two-punch of his work in 12 Years a Slave and Prisoners (where he took a potentially disastrous role and made it work superbly) led me to nominate him for Best Supporting Actor for the latter. There’s a good chance I’ll be nominating him again this year, though for my money, Dano and Cusack must be nominated jointly. As the film progresses, one sees just how the bright-eyed, apple-cheeked Dano and the timid, shrunken Cusack could indeed be the same man, how one became the other, how the latter hearkens back to the former. That the two performances work together so well would alone merit attention.

But the two performances are also extremely good in of themselves. I’m not so familiar with the real Wilson as to comment on the success of Dano and Cusack’s impersonations, but their depiction of a man losing and regaining his ability to control his life rings consistently true, from the panic attack which first portends the tragedy to come, to the final moment of serene reconciliation with Melinda.

Trying to pick which is better misses the point entirely. It is how well they complement each other that matters. If a dual nomination is impossible, then Dano should be nominated lead and Cusack supporting (based on screen-time), but both deserve full credit. Dano embodies young Brian’s search for the sublime as well as Cusack embodies older Brian’s frailty and fear; his mannerisms are absolutely convincing, and in one scene–I will only say it involves a hamburger–his regression is so poignantly spot-on it’s heartbreaking.

The whole cast is really quite good, although there are issues with the writing which keep some of them from reaching their full potential. Most of the 80s half of the film is shown from Melinda’s point of view, a choice which leaves Cusack and especially Giamatti with curtailed screen-time–which is frustrating, since it’s Brian’s story we’re interested in.

That’s not a knock on Banks, however. She shows how much Melinda loves Brian and how difficult it is for her to reconcile that love with the pressure of dealing with Landy. Her first scene, where Brian tries to buy a Cadillac from her, is a very sweet one: she is touched and charmed by Brian, and he by her, but it never plays his illness or her reaction as cute. Often, the camera just focuses on her face and analyzes her reactions to the whole tragic situation, and Banks is quite good at conveying Melinda’s inner conflicts silently. It’s an excellent performance, whatever complaints one may have about the film’s focus.

Giamatti, sadly, doesn’t have all that much to do; what should have been a slam-dunk nomination for him doesn’t quite get there, but not because what he gives us is at all deficient. He shows all the sides of Landy–his slick charm, his violent temper, his manipulations, his domination of Brian–in the time he’s given, and when he’s allowed to be great, he is; the aforementioned hamburger scene is arguably his best as well, as he goes from glib self-promoter to abusive tyrant in the blink of an eye.

But the film really should’ve shown how Brian came under Landy’s thrall, how his treatment became an imprisonment, rather than centered on his relationship with Melinda. Again, Banks is excellent, and she and Cusack work very well together, but their relationship is simply less compelling than that between Brian and Landy.

It’s the script (by Oren Moverman and Michael Alan Lerner) which keeps the film on the lower end of ****½, and not at all because it’s a bad script, but because it’s the most conventional part of a film that otherwise does not adhere to the biopic convention. There are those on-the-nose moments you’d expect (a scene which depicts the inspiration for “Good Vibrations” may be at least rooted in reality, but it’s pretty corny), there’s the issue of focus, and there’s the denouement, which wraps everything up too neatly and quickly, throwing in a little bit of semi-abstract intercutting (which evokes the end of 2001, whether intentionally or not), seemingly to cover the complicated wrangling over Brian’s soul that would have been less cinematic, but might have been more dramatically satisfying.

To be fair, Dino Jonsäter’s editing is at least partially to blame for the weakness of the penultimate sequences, and I have to wonder if there might not be a much longer version of Love & Mercy somewhere out there–at 121 minutes, it’s not exactly truncated, but it could have stood a little breathing room. Elsewhere, the intercutting between eras is quite effective, and enhances the connection between Dano and Cusack’s performances, just as the script is for the most part quite good at exploring the characters and their frequently toxic interrelationships. It just falls short enough to keep the film from becoming unquestionably great.

But Bill Pohlad’s direction brings it awfully close. The two timelines are stylistically quite different, the 80s scenes being shot with clear lighting and crisp composition, while the 60s scenes are often grainy and handheld; the contrast not only suggests the differing cinematic styles of the two eras, but the difference between young Brian, increasingly unstable but still somewhat free, and the older Brian, who is controlled to the point of suffocation. (The compositions are not as crushingly precise as those of Dear White People, however.)

From the opening credits, which strive to appear as those of a 60s film, to the fly-on-the-wall look at Brian’s compositional process (the studio scenes are consistently fascinating), to the counterculture hedonism which only helps to feed Brian’s breakdown, to the horrors of Landy’s abuse and the relief provided by love, Pohlad’s direction gives the film an energy which I appreciated from the very start. Even the weaker scenes towards the end are well handled by Pohlad; it’s the writing which falls short here. It’s kind of amazing that this is only Pohlad’s second feature (the first being the very obscure Old Explorers a quarter of a century ago); a notable producer, I hope Love & Mercy‘s success will lead him to direct again.

Robert Yeoman’s cinematography is excellent, as noted above; Keith P. Cunningham’s production design is especially impressive, particularly in its recreation of the 60s, which to my eyes seemed utterly convincing. It’s likely the team made a lot of use of existing locales (I can’t imagine the budget was all that high), but the period detail, especially the studios, was truly impressive without being at all showy. I don’t know how much makeup Dano or Cusack underwent to resemble Wilson or each other more closely, but I can say the illusion was complete by film’s end.

Atticus Ross provided a score, though the main musical attraction, of course, is the Boys. I only detected Ross’ score on a couple of occasions, and it was quite good–in the vein of his work with Trent Reznor on David Fincher’s recent films, it was discordant and unsettling, mostly to enhance the psychological turmoil on display–but there wasn’t very much of it. I wonder how much Ross was responsible for Brian’s auditory hallucinations, which are extremely well done. (It goes without saying that the sound mixing is excellent; one can usually count on a music-driven film to provide a good mix.)

Before I forget, I want to mention a couple of members of the supporting cast. Mike Love has a fairly bad reputation among Beach Boys fans, mainly for his perceived opposition to Wilson’s experimental drive. Love himself has argued that his opposition has been greatly exaggerated, but the film does not present him in a very good light; he is impatient with Brian’s loftier ambitions and concerned more with commercial viability than anything else. As played by Jake Abel, he’s certainly not likable, but Abel doesn’t let him become a monster, either–Love is shown to have his human side, and to care for Brian, even as he nudges him away from the ether.

And Bill Camp is spot-on as Brian’s father Murry, a sour man, brooding over having been fired as the Boys’ manager and less than supportive of his son’s art. At one point he laughably claims that Wilson and the Boys will be forgotten in a few years, at another that “God Only Knows” sounds like a “suicide note”. Like Abel, he doesn’t make Murry an inhuman monster, just a bitter man trying to milk his son’s talent–as Melinda says at one point, she doesn’t want to be another person trying to use Brian. Abel and Camp show us how some are less conscientious.

An unexpectedly superior biopic, Love & Mercy uses an incredible tandem performance to explore the genius and suffering of one of rock’s greatest innovators. Though it stumbles at times, and doesn’t fully break the biopic mold in the end, it’s more than worth your while.

Score: 86/100

3 Comments Add yours