El Conde/The Count (2023) – ***½

Available on: Netflix

One might well argue that Pablo Larraín’s historical dramas are simply too interesting for the Academy. No, Neruda, Jackie, and Spencer earned a combined five Oscar nominations, none of which were for Picture or Director, and earned a whopping zero Oscars – Natalie Portman’s brilliant performance and Mica Levi’s brilliant score for Jackie were passed over, as was Kristen Stewart’s amazing performance in Spencer. No, the Academy was more enticed by the respectably digestible likes of The Imitation Game, The Theory of Everything, Finest Hour, and The Eyes of Tammy Faye. Pity.

El Conde will likely make far less impression on the awards groups than Jackie or Spencer managed, but it’s not as good as those films – nor is it as good as No and Neruda, which are also rooted in Chilean history. Like No, it’s concerned with the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet (Jaime Vadell), who overthrew the democratically elected Allende government (with American backing) and was responsible for thousands of deaths (and tortures and imprisonments) as well as millions of dollars of embezzlement, for which he was never brought to justice in his lifetime.

What El Conde supposes is that he was a vampire, born in 18th century France as “Claude Pinoche,” who was appalled and radicalized by the French Revolution (especially the execution of Marie Antoinette), and who after years of working against revolutions around the world established himself in Chile, taking the name we know and rising to supreme power before falling from it.

And his supposed death in 2006? An act, and he now lives on a secluded farm, contemplating death after 250 years of life. But after a series of killings in Santiago suggest he’s on the prowl, his five children visit him and his wife Lucía (Gloria Münchmeyer) to figure out just what the old man is up to and to secure their inheritance before it’s too late – and to help sort through his numerous clandestine accounts, a nun and exorcist, Carmen (Paula Luchsinger), posing as an accountant, also arrives.

As Carmen interviews the members of the family, discussing their various shady dealings with little fear (or shame on their part), her presence stirs something in the old “count,” and he considers how to restore himself to youth and make a fresh start – all while Lucía and Pinochet’s old retainer Fyodor (Alfredo Castro) make time behind his back. All these antics eventually get the attention of the Englishwoman who’s been narrating the whole film – but I’ll let you find out who she is for yourself.

Truth be told, the revelation of her identity sums up a lot of what works in El Conde and what doesn’t. It’s an audacious revelation, in keeping with the audacious premise, reflecting a dark sense of humor and a trenchant approach to political satire. But it also feels a bit like the punchline to a sick joke, the kind of thing that would put a nice bow on a short or featurette but doesn’t quite have the weight to anchor a film that pushes the two-hour mark.

There’s much to recommend here, especially for fans of Larraín’s previous work. The boldly absurd premise and the way he uses it to confront the darkness of Chile’s past draw one into the film, but there’s plenty to keep one watching. The performances, while not as dazzling as in his best work, are consistently strong, with Vadell’s ghoulishly unassuming Pinochet holding court and Luchsinger’s bright, unaffected energy underlining the corruption and oppression she outlines for the Pincohets, who variously huff indignantly or smile unashamedly.

Edward Lachman’s cinematography, in generally handsome black and white (some iffy greyscales aside), in league with the palatially decrepit sets, pompous costumes (especially Pinochet’s uniforms and Fyodor’s tuxedo), gruesome gore effects (these vampires prefer eating hearts, especially blended into smoothies), and smartly assembled soundtrack of classical and neo-classical themes, makes an aesthetically pleasing framework for the satire.

And the flying scenes (these vampires fly, as themselves – no transformations here) have a macabre grace, while one scene where a newly vampirized character gradually gets the hang of their ability to fly is lyrically beautiful – and yet, in this context, there isn’t so much room for the lyrical, and it feels at once enchanting and extraneous.

The film’s high points of satire and grotesque humor are undermined by its messy story, which begins to unravel rather badly towards the end, as the characters’ motivations become muddled and reversals of fortune occur for little clear reason except to move us closer to the finish line. The final joke lands, of course – and reinforces one of the film’s key points, that we are never truly free of oppressors like Pinochet – but again, the film feels like a good short stretched too thin. (Larraín co-wrote the script with Guillermo Calderón; his work here and in his 2019 film Ema suggests that writing is not his strength.)

Curious viewers who come upon El Conde on Netflix may be reassured; Larraín and Calderón do enough scene-setting to bring non-Chilean viewers up to speed. But I found myself wondering why I responded more strongly to Larraín’s two distinctly non-Chilean films. Is it perhaps that, it dealing with the stories of Jackie Kennedy and Princess Diana, Larraín was able to get past the mythologizing of them, was able to be more objective about the histories of America and Britain? Or is it just me?

Score: 79

Outlaw Johnny Black (2023) – **½

I struggled with Outlaw Johnny Black in a lot of the same ways I struggled with El Conde, only to a greater degree; while unofficially touted as a spiritual sequel to Black Dynamite, which is directly cited on the poster, it doesn’t do for the Western what Dynamite did for Blaxploitation – nor, much of the time, does it seem like that was the intention. But what the intention was is hard to say, and that uncertainty makes the already excessive 130-minute running time feel all the longer.

Johnny Black (Michael Jai White, who also directed and co-wrote) has been on the trail of Brett Clayton (Chris Browning) since Clayton killed Johnny’s father Bullseye (Glynn Turman) years earlier. After being accused of killing a local sheriff (despite only shooting the man in his hat), Johnny narrowly escapes execution with the help of Native Americans he’d defended from racist bullies. Fleeing into the desert, he nearly dies, but is rescued by Reverend Percy (Byron Minns, the other co-writer), who’s on his way to Hope Springs, Oklahoma to take over the local church and marry Bessie Lee (Erica Ash).

After another group of Natives seemingly kill Percy, Johnny escapes and assumes Percy’s identity, arriving in Hope Springs and finding it difficult to pose as a preacher – and finding the town to be under the thumb of the ruthless Tom Sheally (Barry Bostwick), with only the legally savvy Jessie Lee (Anika Noni Rose) able to keep him at bay. Then Percy arrives, after escaping a forced marriage, and Johnny pressures him to pose as his deacon (named Deacon Deacon) until he can get his hands on the church’s money and leave town.

But of course, things don’t work out as planned, and Johnny’s conscience – along with Jessie’s growing interest in him – lead him to defend the town from Sheally and his men…which includes a hired band of marauders led by Clayton, giving Johnny a chance to finally avenge his father.

The biggest issue with Johnny is one of tone. Especially if you compare it to Dynamite, there’s a fundamental uncertainty as to how seriously we’re meant to take what happens throughout the film. For every moment that aims for the overripe badassery (a scene where Johnny slaps around a henchman while repeatedly stealing his gun is a highlight) or self-aware genre parody (the increasingly over-populated finale) which defined Dynamite, there’s two or three which aim more for a wry tone, or even for sincere drama, as when Johnny channels his father’s preaching abilities.

These clashing tones could be balanced successfully (Rio Bravo comes to mind, though it’s considerably more grounded in its humor), but Johnny doesn’t pull it off, and while there are definitely funny moments here, it’s not funny enough often enough, and the comic moments are rarely realistic enough to not undermine any attempt to take what’s happening seriously.

When Johnny is trying to bluff his way through his first appearance in Hope Springs, what could’ve been a really funny scene falls rather flat; he’s not wildly inappropriate enough to make it work as a farce, and he’s too cluelessly inept for it to work as character comedy – especially since we already know his father was a preacher!

Scenes which directly riff on the genre also tend to stumble; the gag in which Johnny points out he shot the sheriff’s hat is repeated without an actual payoff, and the meta-gag of casting white and other non-Native actors as Native Americans isn’t delivered skillfully enough to land. No amount of skill, however, would save the scenes where Percy is forced to marry a Native “bride” (Rigan Machado); whether the scene plays for you as transphobic (Machado is a cis male), homophobic, or simply as mocking Machado’s character for her burly appearance, it leaves a sour taste in the mouth.

The acting helps keep it afloat. White is better at playing the glowering badass than the reformed agnostic, but he’s got charisma to burn. Minns brings a spirited humor to Percy, and Ash makes Bessie’s barely repressed infatuations sympathetically amusing. Browning is a genuinely creepy, cold-blooded villain – a villain who does it for the love of cruelty – and Bostwick enjoys playing the unrepentantly greedy Sheally. Kevin Chapman as the oafish but essentially decent marshall, Turman, and Eme Ikwuakor as the addled Elmer stand out among a solid supporting cast.

As a piece of filmmaking, it’s shaky, with decent sets and costumes, a solid score (I’m not sure what was written for the film and what wasn’t), and effective sound, but some iffy cinematography, especially in the fight scenes, which are framed far too tightly, at least one really bad bit of CGI, and of course the editing, which allows the film to run far too long. It’s not boring, but it’s shaggy and meandering, which doesn’t make for great thrills or laughter.

Those problems, though, are rooted in the script, which never quite seems to decide what kind of story it wants to tell, or how. Dynamite had the guiding hand of director Scott Sanders, whose only subsequent feature, Aztec Warrior, seems never to have been released. Whether he would’ve made Johnny better is anybody’s guess, but while I don’t think Dynamite is unimpeachably great, it knows what it’s doing and moves so quickly – from the streets to Kung Fu Island to the actual White House – that you can move past its weaknesses.

Johnny has its compensations, no doubt, but they’re not enough – for me, at least – to get past the fundamental uncertainty which keeps it from catching fire. Your mileage may vary – but I’d say you can wait to find out.

Score: 63

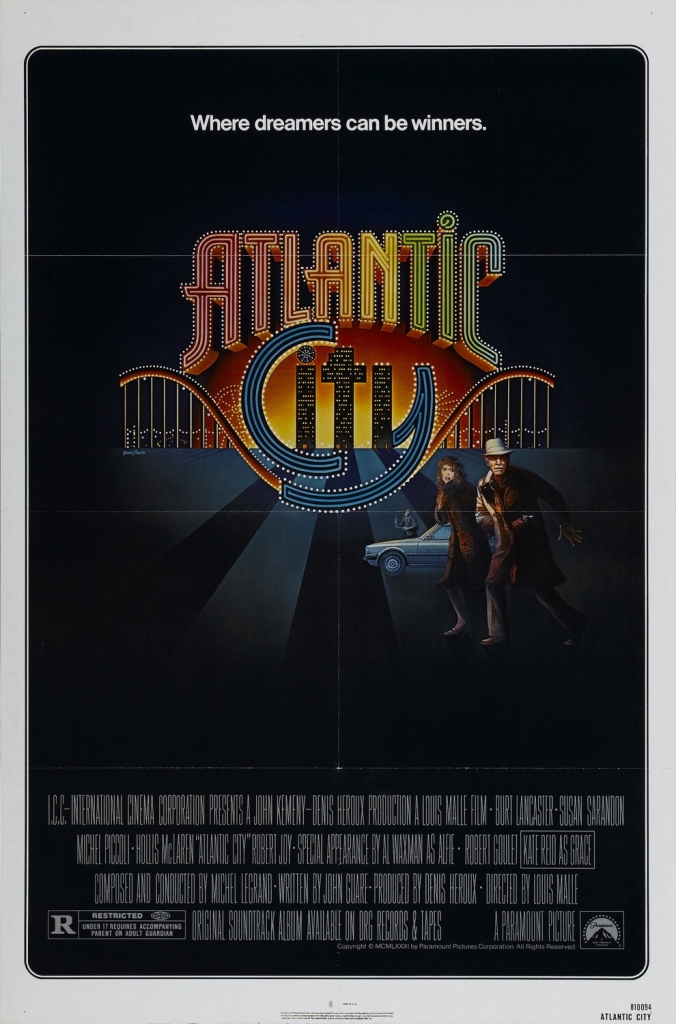

Atlantic City (1980) – ****

Available on: Kanopy

At the time, Atlantic City was a pretty big deal, especially for the awards groups; it earned the “Big Five” Oscar nominations and won a number of critics’ awards, especially for John Guare’s screenplay and Burt Lancaster’s performance – his first significant awards attention since Birdman of Alcatraz almost 20 years earlier. But in the 40 years since, it seems to have been, if not forgotten, increasingly overlooked. And watching it, I’m less surprised by that than by the degree to which it was embraced at the time.

Not because it’s a bad film, mind you; it’s a very fine one indeed. But because it’s a low-key film, one which takes its time to work its magic on the viewer, one which doesn’t really have a big moment or classic line to help cement it in the popular consciousness. Even Chariots of Fire, which actually won Best Picture that year despite being a fairly forgettable film, has that legendary Vangelis score.

And to be sure, I went into Atlantic City relatively cold, not entirely sure what to expect – I knew Lancaster plays an aging low-level gangster and Susan Sarandon plays a waitress who catches his eye. But I think I expected a neo-noir, something gritty and suspenseful, something closer to director Louis Malle’s Elevator to the Gallows or his New Wave colleague Godard’s Breathless (or their colleague Truffaut’s Shoot the Piano Player).

The film begins with Sarandon (as Sally) cutting lemons and rubbing them on her arms and chest; she works at an oyster bar, and this is the best way to get the stink of the shellfish off her skin. She listens to classical music (an aria from Norma) as she does, and Lou (Lancaster) watches from his window (they’re neighbors). The music, Sarandon’s beauty, Lancaster’s charm, and the very nature of the scene might make you think this is romantic – or make you think it’s trying to make you think it’s romantic.

It’s creepy and pathetic, of course, but it’s not until later in the film, after all his rhapsodizing about how great Atlantic City used to be and his boasts about the famous gangsters he’d known, that we learn that Lou isn’t a has-been but a never-was, that he’s a lot closer to Buddy (Sean Sullivan), the bathroom attendant whose eternally boyish good humor is all the more haunting contrasted with the meager living he makes, than he’d ever want to admit.

Sure, Lou has class of a kind (or “floy floy” as he’d put it, quoting an old song), but like the old Atlantic City, which is rapidly decaying and being cleared away throughout the film, his time has passed. He’s not really fighting it, either; he misses the old days but takes care of Grace (Kate Reid), the eccentric, demanding widow of his memorably-named associate Cookie Pinza, and he runs a numbers game because, well, that’s what he has to do.

Sally has her own problems. She’s training to be a card dealer under the watchful – too watchful – eye of Joseph (Michel Piccoli), but her life is upended by the reappearance of her estranged husband Dave (Robert Joy) and her pregnant sister Chrissie (Hollis McLaren). Dave is the father, just one aspect of his overwhelming irresponsibility, which extends to stealing drugs from dangerous men and reselling it (with Lou’s help, much to the buyer’s amusement).

With Felix (Moses Znaimer) and Vinnie (Angus MacInnes) on his trail, Dave ends up dead, and Lou offers Sally his help (with the money he made from selling the drugs), using this opportunity to get to know the young woman he’s only seen from afar. He also brings Grace and Chrissie together; Chrissie’s gentle, flower-child nature and skills at therapeutic massage are just what Grace needs – and Grace finds in Chrissie someone who really needs taking care of, someone who can really bring her out of the self-absorption she’s fallen into.

So even with the romantic elements of Lou and Sally’s relationship, and even with the continuing threat posed by Felix and Vinnie, this isn’t so much an age-gap romance or a thriller as a story of people who need one another, who need to care about each other and find reasons to believe in themselves. That Lou will find a darkly comic reason to do so is part of the fun – and part of why the film doesn’t slide into sentimentality.

It does stumble in showing just how blithely spiritual Chrissie is, or how histrionically pushy Grace can be; at times, Guare’s script errs on the side of schtick. But at other times, the eccentricity works beautifully, like when Sally is trying to get ahold of Dave’s parents but can hardly hear herself think because Robert Goulet is caterwauling right next to her. That’s Atlantic City for you.

And any lapses in the writing are compensated for by the fine performances. Lancaster, earning his last Oscar nomination, at once draws upon his star power and subverts it, as when Lou is confronted with his own inadequacies; he’s at once charming, faintly absurd, pathetic, and weirdly endearing. Sarandon, earning her first, shows through her own star power how Sally has the potential for greater things, while displaying the vulnerability which Dave and Joseph attempt to exploit. McLaren, Reid (some awkward looping aside), Joy, and Sullivan are all convincing in their own right, adding depth to a film which grows on me the more I think about it.

While I can’t quite consider it one of the all-time greats, I really did enjoy Atlantic City. It’s the kind of film that goes down unexpected paths, playing out in a way that feels right, surprising you without needing to throw curveballs, and ending the way it should – with the end of the old Atlantic City seen now not as a tragedy so much as the simple passage of time.

Score: 88

2 Comments Add yours