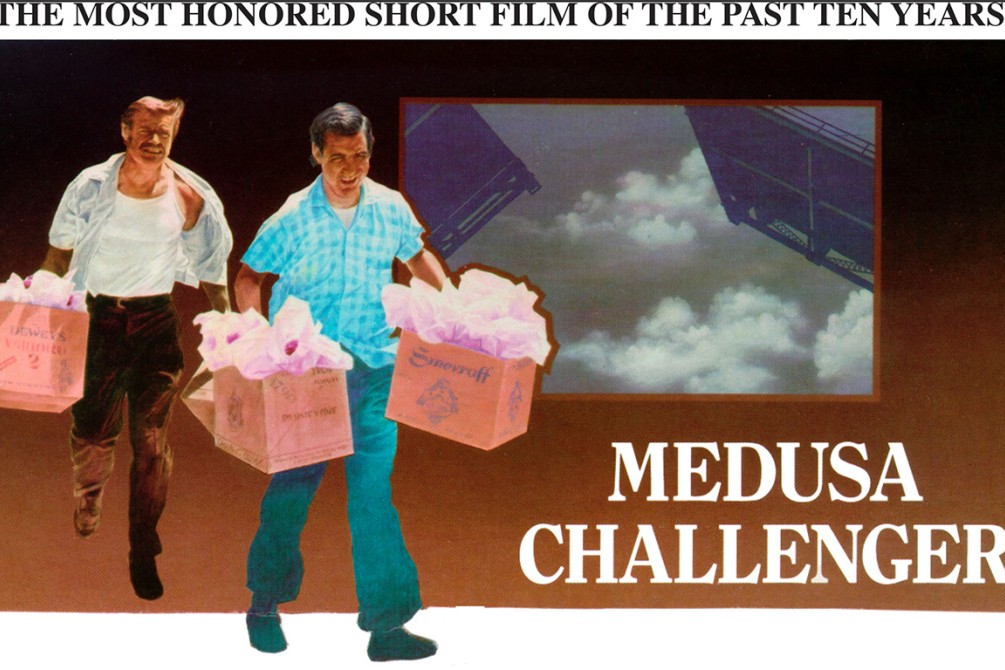

Medusa Challenger (1976) – ***

Last week I reviewed a little-known short film which marked the screen debut of Christopher Walken; this week I review a (now) little-known short film which marked the screen debut of Joe Mantegna. He plays Joey, a mentally handicapped young man who helps his uncle Jack (Jack Wallace) sell carnations in the streets of Chicago. While plying their trade on the Lake Shore Drive drawbridge, they’re separated when the bridge opens to allow the Medusa Challenger cargo ship to pass. Jack is sick with worry, but Joey gets an idea and makes a little victory out of the situation.

Well received and amply rewarded at the time (at least by festival juries/audiences) it now works mainly because of the two leads; Mantegna, in a role that could’ve slipped into caricature, is really quite affecting and effective (his nervous physicality is especially convincing), and Wallace (who had dozens of credits over the years, mainly in small roles) has one of those faces that just radiates character, even before he lets a cigarette dangle from his lips, or steals a rowboat to try and get back to Joey.

Director Steven Elkins’ script, however, feels a bit thin and shallow, even considering the 24-minute running time; there were opportunities to dig deeper into these characters, like when Jack makes a detour to chat up the bridge operator, who’s an old friend, just as there were opportunities to flesh out the story more – instead, we spend more time than really necessary on shots of the bridge opening (including one admittedly impressive bit where the camera is mounted on the middle of the bridge as it rises into the air) and of Jack and Joey moving through traffic, hawking their wares.

Alan Barcus’ score, which ladles on the emotional strings and folksy piano, reflects the good intentions which pervade the film, but ultimately feels like an attempt to add significance to what’s ultimately a pleasant but forgettable anecdote. But hey, it’s always nice to see Chicago on the screen.

Score: 71

The Philadelphia Story (1940) – ****

I don’t suppose The Philadelphia Story needs much introduction. It’s been a classic since the day it opened, winning Oscars for its script and for James Stewart (more on that in a moment), meriting a musical remake (High Society), a place in the Criterion Collection, and spots on the AFI’s lists for best romances, best comedies, best romantic comedies, and best American films. And according to the BFI, it’s Lars von Trier’s favorite film. Whether that’s a point for or against it I’ll leave to you.

It’s not that Lars doesn’t have good taste in this department—it overflows with witty dialogue, old-school star power, and glossy charm, with a streak of grounded humanity in the journey of Philadelphia socialite Tracy Lord (Katharine Hepburn) from high-minded judgment to a happier, wiser state of mind, with the help of “Miss Pommery 1926” and reporter Macaulay “Mike” Connor (James Stewart), who’s been assigned to profile her wedding for a respectably trashy magazine. He doesn’t want to be there and she doesn’t want him there—at first. (In a twist on the mistaken-identity trope, he’s pretending to be a friend of her brother’s, but she knows his secret – and gives him a hard time before the truth comes out.)

But as we get to know everyone involved and Tracy and Mike get to know one another, we start to wonder who Tracy will be happiest with: her fiancée, self-made coal tycoon George Kittredge (John Howard), who’s still adapting to Tracy’s aristocratic lifestyle, Mike, or her ex-husband C.K. Dexter Haven (Cary Grant), who’s still friends with the rest of the Lord family, and who might just carry a torch for Tracy, if she can only loosen up a bit. Throw in Mike’s photographer Liz Imbrie (Ruth Hussey), who carries a torch for him, Tracy’s highly observant little sister Dinah (Virginia Weidler) and roguish uncle Willie (Roland Young), and the ample influence of “Miss Pommery” and you’ve got a romantic comedy for the ages.

Indeed, despite a few aspects which haven’t aged well – Willie’s overbearing attentions towards Liz strike an especially sour note now – The Philadelphia Story remains quite fresh and accessible to this day. The idle rich are still very much with us – and growing even richer by doing their idling on TV and social media (though Tracy would doubtless find such behavior vulgar), and the intolerance of other’s shortcomings, which Tracy can only overcome by being confronted with her own fallibility, is about as timeless and universal a theme as you could wish.

It helps that the film’s comic elements are comparatively grounded; Dinah’s showing off for Mike and Liz is hilarious in part because it feels so authentically performative, with her speaking in the poshest voice possible before banging on the piano and belting “Lydia, the Tattooed Lady.” And scenes like a very drunk Mike waking Dexter up to dish out dirt on Mike’s slimy publisher have something like the real anti-rhythm of giddy drunkenness. It’s a funny film, but you laugh with the characters as much as at them.

This helps the film work as a romance as well; since we can believe in the characters as people, we can believe Mike’s growing infatuation with Tracy, Dexter’s frustrated affection, and George’s idealistic worship of her – which, if it needed to be made more clear, makes him wholly unsuited to marry her. But even if John Howard was never going to get the girl over James Stewart and Cary Grant, the question of which of them will end up with Tracy isn’t answered until the very end – and the script takes care to justify her choice.

Maybe too much care, for if there’s a major weakness with the film, it’s that Donald Ogden Stewart’s script, from Philip Barry’s play, hews just a bit too close to the structure and pacing of the original. At 112 minutes, it’s just a bit long for a light comedy, and as the film mostly takes place in and around the Lord estate (there’s not much of Philadelphia in the film, per se), and has more sitting/standing around and talking than real action…it’s just a bit poky at times, at least for me.

So maybe George Cukor didn’t need his Oscar nomination for Best Director, and maybe (Donald Ogden) Stewart didn’t need the Oscar over the scripts for Rebecca and The Grapes of Wrath (which I haven’t seen, to be fair). And no, (James) Stewart didn’t really need to win an Oscar for his work here; he’s charming and earnest as always, leavened with a bit of snark, but then and now it’s generally felt he won because he’d lost the year before for Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. (That he wouldn’t win for his later, greater performances in It’s a Wonderful Life, Harvey, and Anatomy of a Murder doesn’t help.)

But Hepburn was a worthy nominee as Tracy, a role literally written for her and her ability to combine patrician affectation, acerbic wit, romantic warmth, and comic anxiety. And while I’d probably have nominated the wonderful, scene stealing Weidler for Supporting Actress over Hussey, Hussey ably delivers her one-liners and conveys her feelings for Mike without slipping into self-pity. As for Grant, he wasn’t nominated at all, despite bringing all his own grace and comedic timing to the table, laced with a sincere tenderness which gives his scenes with Tracy a poignant weight. Young, Howard, Mary Nash as Tracy’s breezily proper mother, and John Halliday as her politely philandering father round out the excellent cast.

And it was a worthy nominee for Best Picture, even if Rebecca rightfully won. I’ve spent a lot of words detailing the strengths of Story (and its modest flaws), but if you’ve seen the film, and you certainly should, then you know that the only word for it is yare. Easy to handle, quick to the helm, fast, bright…everything a film should be.

Score: 90

How to Blow Up a Pipeline (2022) – ****

From a sparkling romantic comedy about the upper crust of society to a trenchant thriller about angry young people conducting industrial sabotage is, to be sure, a hell of a pivot, but it’s the kind of pivot I’ve tried to build my brand on. Maybe I’ll rewatch the 1967 The Jungle Book next. I need to, after all.

But I digress. That I described Pipeline as a thriller should tip you off that, the incendiary title notwithstanding, this is not a documentary, or in any way an instructional film, but the book by Andreas Malm which inspired the film isn’t a guide to sabotage either, just an argument in favor of it. The film, for better or worse, keeps the political theory relatively light, preferring to ground its characters’ radicalization in personal stakes.

Theo (Sasha Lane) is dying of leukemia, possibly caused by industrial pollution. Her best friend Xochitl (Ariela Barer) is motivated by that, and by the death of her own mother during a heat wave (possibly caused by climate change). Theo’s partner, Alisha (Jayme Lawson) has great reservations about the whole operation, but chooses to stand by Theo. Shawn (Marcus Scribner) is motivated partly by Xochtil’s radicalization, and partly by the stories of those affected by pipelines, which he hears through his work on documentaries.

One of the people Shawn meets is Dwayne (Jake Weary), who’s forced off his family’s land (via eminent domain) to built the pipeline the characters are planning to attack. And speaking of land, Michael (Forrest Goodluck) lives on Standing Rock Reservation in North Dakota, picks fights with Dakota Access Pipeline workers, butts heads with his family for not being forceful enough, and finally starts teaching himself how to build bombs, establishing an online presence which brings him to Xochitl’s attention.

Finally, there’s Rowan (Kristine Froseth) and Logan (Lukas Gage), who initially seem to be the most immature, performatively radical, and least trustworthy of the bunch. But there’s more to the two of them than we initially realize, and there’s more to the film than a simple call to arms.

As we follow the characters over the few days leading up to their operation, we get their stories in brisk flashbacks, brisk like just about everything in the film, which packs a great deal into its 104 minutes. Perhaps it even tries to do too much, or perhaps the script, co-written by Barer, director Daniel Goldhaber, and Jordan Sjol, doesn’t quite strike the steadiest balance between being a piece of message-driven political cinema and a character-driven thriller. When the characters do discuss their politics, it tends to feel like self-conscious posturing – which might well be the point, but it doesn’t entirely come off.

But the film is focused more on these specific people, the specific course of action they choose to take, and the psychological pressure and physical danger involved in doing so. The scene where Michael prepares the blasting caps is especially nerve-wracking, as the powder involved is so volatile that simply spilling it could cause a small explosion. He may put on a stoic, even nihilistic face, but the sheer anguish of this sequence cuts right through that. (Goodluck is excellent throughout.)

It’s also willing to explore the question of how qualified these characters are to take such action – Alisha describes Xochitl as “another girl who went to college, read a book, and decided she knows how to save the world,” and it’s hard to argue – and whether this kind of sabotage will actually help anything, or if the incremental grassroots efforts of activists like the colleagues Xochitl angrily leaves behind are, indeed, the wiser course. The film sympathizes with sabotage, no question – and cites how activists of the past, once demonized, are now lionized – but it leaves you the room to really engage with its subject matter.

It’s also a crackling entertainment, thanks to Daniel Garber’s crisp editing, Tehillah De Castro’s sharp cinematography (from the stark West Texas scenery to the old-school zooms used in the climax), Gavin Brivik’s haunting, synth-driven score (definite shades of Blade Runner), and Goldhaber’s taut direction. To be sure, if all you’re looking for is a good thriller, you might be better off looking elsewhere – the political aspects are too front-and-center to compartmentalize – but then, if that’s the case, the title probably put you off before you read this far.

A good ensemble cast helps. Goodluck and Lane, who’s poignantly out of fucks to give as the weary Theo, are the MVPs in my book, but Weary as the quietly intense Dwayne and Lawson as the devoted Alisha are very effective in their own right. Froseth and Gage are perhaps a bit too good at being annoying early on, though they’re up to the task when the script gives them more to work with. Scribner is all right, but Shawn is unfortunately the least interesting of the principals as written; Barer, despite co-writing, co-producing, and being arguably the closest this ensemble piece has to a lead, might be the weak link in the cast, unless we’re meant to consider the possibility that Xochitl is, indeed, somewhat in over her head. (She’s not bad, but I never completely believed in the character.)

Quibbles aside, Pipeline is a fine, timely film, sneaking into the low end of ****, not so much because it has an important message, but because it develops a story which bears its weight. If it doesn’t rank with the very best radical cinema, it’s still damned funny to realize this is playing in the same theaters as Air.

Score: 87

Beau is Afraid (2023) – ****

A pro-tip: if nature calls during Beau is Afraid, the first time he runs into the forest (after the paint scene) is a good time to step out.

I’ve now seen Beau is Afraid twice, once with a decent-sized, fairly receptive Thursday night audience, once with a fairly small Friday night audience composed of young men, two of whom chattered inaudibly throughout the film. Otherwise, they didn’t laugh or gasp or react in any particular way.

That probably fits, given that Beau is the kind of film which will work quite well for some, baffle others, and bore still others – not totally without cause, as the film runs just under three hours and, especially towards the end, starts to feel like it. But it worked quite well for me, not just because I’m more inclined to embrace this kind of ambitious/self-indulgent auteur enterprise, but because I was able to sympathize with how it depicts the crippling effects of anxiety, insecurity, and guilt.

Beau Wassermann (Joaquin Phoenix) needs to get home to visit his mother, Mona (Patti LuPone); it’s the anniversary of his father’s death, the circumstances of which a younger Mona (Zoe Lister-Jones) narrates in a grotesquely funny monologue deep into the film. But even before he sets out, things begin to go wrong: a neighbor demands he turn down music he isn’t playing, playing loud music in response which causes Beau to oversleep; his keys and luggage are stolen, and the water in his building is shut off, leading him to be locked out while a crowd of strangers invade his apartment and throw a raucous party while he watches helplessly from a scaffold. Then he gets the news that Mona is dead, her head crushed by a chandelier. Then a man, clinging to his ceiling, falls on him while he’s taking a bath.

Oh, and there’s a brown recluse in his apartment.

Beau flees and is hit by a car (and stabbed), then cared for by the irrepressibly plucky surgeon Roger (Nathan Lane) and his wife Grace (Amy Ryan), who are as kind to him as their daughter Toni (Kylie Rogers) is resentful of his being given her room. After that interlude, and with the wrathful commando Jeeves (Denis Ménochet) on his tail, Beau flees and finds himself among the Orphans of the Forest, a group of traveling players, and imagines himself the protagonist of their allegorical play, which takes him on a decades-spanning journey of loss, love, loss, travail, and so forth.

Eventually, he’ll get to Mona’s house, and the twists and turns will just keep coming, culminating in a literal trial where Beau’s smallest sins are used against him. In keeping with the film’s overarching themes of guilt and paranoia, Beau is confronted with the fact that those deeds which he might have thought were forgotten, or not so bad, are very much remembered and even worse than he imagined.

Imagine every anxious thought that kept you up at night writ large, imagine that every time you were told “it’s all right” or “it’s not a big deal” it was a lie, imagine that every fear you had about the world and especially about other people – namely that they hate you with little or no cause and will not hesitate to bring you down – was absolutely justified, and you’ve got some idea of the existential horror at play in Beau.

Phoenix is, of course, perfectly cast as Beau, the apocalyptic nebbish who can’t seem to do anything right, and who can’t make anything better because the world is so cruel and his efforts are so ineffectual. That sounds unbearably pathetic, but Phoenix’s performance is by turns poignant, funny, and oddly endearing; Armen Nahapetian is also quite good as the younger Beau, who’s just as nebbishy but hasn’t yet calcified into the misery of his older self.

But the whole cast is excellent, with LuPone as the Biblically implacable Mona (the Jewish mother distilled to a pot of vinegar in a black dress) matched by Lister-Jones as the gentler but still manipulative younger Mona, whose wishes and intentions regarding her son are as ambiguous as the reality of everything that happens in the film – and I’m prepared to say nothing here can be taken as objective reality. It’s an epic nightmare, a three-hour dramatization of a persecution complex, a world in which Mona is God and Beau is something like Job, or Jonah, or worse.

Lane is a delight as Roger, savoring every moment of suburban-dad quippery (“It’s beddy-bye time for the Rog-man!”), Ryan ably hints at the greater depths to come, and Rogers’ depiction of teenage angst taken to the nth degree is at once hilarious and chilling. Stephen McKinley Henderson uses his broad, warm smile to unnerving effect as Beau’s therapist, Parker Posey brings a measure of warmth to her role as Beau’s great lost love Elaine (as does Julia Antonelli as her younger self), and Richard Kind shows how well he can play a cold-blooded bastard as the Wassermann’s attorney.

Writer-director Ari Aster crafts some of the finest scenes of his career so far; the urban nightmare of the first act, the extended flashback to the cruise where Beau and Elaine met, and the play he dreams himself into (realized with stylized sets and animation) are all brilliantly realized. Fiona Crombie’s ambitious and fascinating production design, Pawel Pogorzelski’s cinematography, Bobby Krlic’s score, and some superb makeup and special effects all add to the effective realization of Aster’s vision. And, despite the excessive length, Lucian Johnston’s editing is often beautifully managed.

Yes, it’s a flawed film, one which is perhaps just a bit less than the sum of its parts, one which could’ve stood a little tightening, at least in certain segments, and which fades just a bit as it goes from potential ending to potential ending, until the final scene arguably feels truncated simply because it’s time to wrap it all up.

But it’s still a film full of greatness, full of funny details (“O’Loha,” the Hawaiian/Irish TV dinner; the nod in the name “Wassermann” to the obsolete test for syphilis), impressive imagery, excellent acting, and themes worth pondering. I recommend it.

Score: 88

Love The Philadelphia Story.

What do you think about the other Cary-Kate romantic comedies?

I had mixed feelings about Bringing Up Baby when I saw it, but I need to give it another look. I haven’t seen Holiday yet, but it sounds more to my taste.

I revisited Holiday last year and really loved it — actually moreso than the first time I saw it on TCM back in the day.

Bringing Up Baby has some things that don’t work (IE the drunk Irishman) but a lot of it is so good, so perfect.

The late Peter Bogdanovich did an extremely entertaining Bringing Up Baby audio commentary.

Ps. did you see that I covered one of your favorite films (A Touch of Sin) on my Substack a while back?

Hope you’re doing well.

Lately I’ve been getting into the films of Jim Jarmusch. Also digging into the Bruce Lee Criterion box set.

I want to tell you something — I’m very impressed by your continued productivity on this blog. For me, it would be very difficult to just keep putting something out that frequently.

I hadn’t seen that! I’ll take a look. I really need to rewatch it, haven’t seen it since it was in theaters.

And thank you. Truthfully, I sometimes feel like I’m slacking when I only see 3-4 films in a week, but sometimes that’s all I have the energy for.