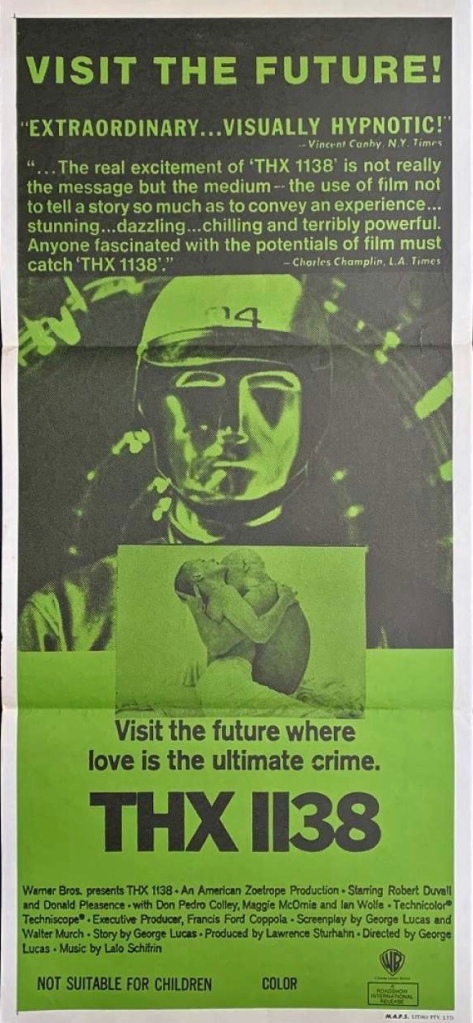

THX 1138 (1971) – ***

Maybe I was just tired. Sitting on my couch, letting THX 1138 wash over me, I was at once impressed – by how fully the film achieves its vision of a future in which the human race is permanently benumbed – and exasperated – by how benumbing that actually is to watch for an hour and a half. George Lucas made this, one of the most abstract releases from a major studio I’ve ever seen, at the start of his career (it’s based on a short he made as a student); he’d follow it with the infinitely more commercial and commercially successful American Graffiti and Star Wars.

When I rewatched Star Wars, I noted that Lucas’ writing held the film back; he just doesn’t have the knack for crafting dialogue that does more than move the story along. He didn’t write THX by himself – he co-wrote it with Walter Murch, himself best known as an editor and sound designer – but the premise seems the perfect fit for his writing abilities; the dialogue is made up mostly of technical jargon, rote recitations, and the blunt, fragmented speech of this future society.

The basic story is easy enough to follow. THX (Robert Duvall) is a technician, kept docile like the other members of this society through a regimen of sedatives and pervasive social conditioning. His roommate, LUH 3417 (Maggie McOmie), has begun to rebel against their situation, and meddles with THX’s sedatives, allowing him to feel emotions – and to fall in love with her. Their colleague, SEN 5241 (Donald Pleasence), tries to get THX assigned as his roommate, which THX rejects.

After an incident at work, THX is charged with “illegal sexual activity,” his affair with LUH being known to the authorities – and sex being against the law. He is placed in a prison, a vast white void, where the inmates sit idly. Among them is SEN, who tries to encourage them to rebel, but has no notion of how. Finally, THX decides to simply leave, and the film climaxes with his unusual escape from the city and his final emergence onto the surface, where he sees the sun for the first time in his life.

Rewatching the film, I can appreciate it a bit more, and am raising my score from a high **½ to a mid-low ***. I can more clearly see the touches of topical satire woven into the story: the android police, so clearly modeled on the cops in riot gear who clashed with the counterculture, speak anodyne phrases in a soft, artificial voice, are prone to malfunction, and finally let THX go at the end because the operation to capture him has gone over-budget! There’s also the supervisor who casually disclaims any responsibility for putting THX in a “mind-lock” – which nearly causes a catastrophic accident – and the cheeky touch of having SEN’s rants drawn from Nixon’s speeches.

I appreciate the imagery even more; just as Cronenberg made good use of the Brutalist architecture he found around Toronto in Stereo and Crimes of the Future, so Lucas and his team made use of locations in and around San Francisco, including the unfinished tunnels for the BART system, a telephone exchange, and various examples of Modernist architecture which reflect the bright white sterility of this world. (It helped that I watched the unaltered version; Lucas’ tweaks for the DVD release are unnecessary at best and damaging at worst.)

The cinematography by David Myers and Albert Kihn, in league with the editing by Lucas and his then-wife Marcia, creates an atmosphere of alienation and disorientation that I found frankly overwhelming on first viewing. Shots are frequently framed off-center, or feature distorted security footage, or extreme close-ups of computer read-outs, sound waves, and so on; the most famous images from the film come from the prison scenes, where the blank expanse of the setting makes it rather hard to get one’s bearings, and the camerawork deliberately keeps us off balance.

The editing, meanwhile, reduces many scenes to brief beats, or cuts the action counterintuitively; it’s hard to put into words how it works, but the effect is slightly like when I read The Einstein Intersection, knowing that Samuel R. Delany is dyslexic – it’s not that the words (or in this case images) don’t fit together, they just fit together in a different way than I’ve previously experienced. I think of what Truffaut said of Tati’s brilliant Playtime: “a film that comes from another planet, where they make films differently.”

The acting is likewise tricky to evaluate, given the nature of this society. Pleasence is ideally cast as SEN, playing up the quirks of the role and initially hinting at the possibility of sinister and/or sexual motives, but later revealing how pathetic SEN really is. He, along with Don Pedro Colley as the affable hologram actor SRT 5752 – who seems not to have been subject to the same conditioning as the others – bring some lively humanity to the table.

My mother always praised Duvall for his chameleonic skills, and he certainly gives himself over to the demands of the role, betraying no conventional emotion as THX moves uncertainly towards his ambiguous fate. That it’s hard to get truly invested in his journey is not Duvall’s fault; the material and approach just don’t allow for it. McOmie had no other major film roles (she was mostly a stage actress), but she’s okay as LUH; her face can’t help but suggest deeper feeling.

The film is really a showcase for Lucas’ vision, for Murch’s sound design, which is extremely impressive, both in the effects (the whine of the police cycles in the final chase is especially memorable) and for how he layers the radio chatter, the ambient sound, and Lalo Schifrin’s eerily quirky score. It’s far from a great film, but it shows a side of Lucas we sadly never really got to see again.

Score: 69

Armageddon Time (2022) – ***½

I think I’ve said before that coming-of-age films, especially those which serve as thinly veiled memoirs for their directors, have never quite been my cup of tea. Such films are usually solid, but rarely live up to the praise they often receive – Lady Bird, Roma, Minari, and Belfast are all good films, but they resonated far more strongly with others (namely the critics and awards groups) than with me. And I may have mentioned that the works of James Gray have never quite clicked with me either; like Aronofsky, he makes the kind of films I want to like, but something about them falls short of real greatness for me.

But I’d seen his last three films and liked each markedly more than the last. The Immigrant was mid-low ***, The Lost City of Z was high ***, and Ad Astra was mid-high ***½. As such, I had some hope that Armageddon Time might finally take the leap into **** territory, though the reviews were just soft enough to keep my expectations in check. And, sure enough, it doesn’t quite get over the top, in part because it falls victim to the same issues which hampered its brethren. But it gets fairly close, because it has many of their virtues as well.

In 1980, Paul Graff (Banks Repeta) is a sixth-grade student in Queens, rubbing his thin-skinned teacher Mr. Turkletaub (Andrew Polk) the wrong way and befriending Johnny (Jaylin Webb), who’s repeating the grade and is regularly in trouble with Turkletaub. Paul’s Jewish-American family places a lot of pressure on him and his older brother Ted (Ryan Sell) to succeed; Ted attends a prestigious private school, and Paul’s grandparents urge his parents Esther (Anne Hathaway) and Irving (Jeremy Strong) to take him out of public school and enroll him in Ted’s school, which Paul resists.

However, after Paul and Johnny are caught smoking pot in the bathroom, he is forced to enroll in the private school; when Johnny, having dropped out of school altogether, pays Paul a visit at his new school, Paul’s new classmates make racist comments about him (Johnny is black). They remain friends, and to avoid being sent into foster care, Johnny (who had been living with his ailing grandmother) sleeps in Paul’s backyard clubhouse.

Paul, meanwhile, struggles to fit in at school and balance his passion for art with the expectations of his teachers and family. His relationships with Esther and Irving are frequently contentious, and he’s closest to Esther’s father Aaron (Anthony Hopkins), who tells Paul about how his own mother fled her native Ukraine because of anti-Semitism. But when Aaron’s health fails, Paul, having heard Johnny’s stories about his half-brother in Florida, hatches a fateful scheme to run away.

Although the film is based upon Gray’s own youth, right down to the family softening their name for the sake of assimilation (“Gray” was once “Greyzerstein”), it also has some parallels with the 1975 Canadian film Lies My Father Told Me, namely the young protagonist having a warmer bond with his doting grandfather than with his status-obsessed parents. And in both films, the grandfather dies and is last seen in the mind’s eye of the protagonist – there symbolizing the simple happiness that has been lost, here reminding him and us of the wisdom that will endure.

Part of the wisdom Paul gains in the course of the film is an awareness – bitter but vital – of the unfairness of life and the human frailty of the adults around him. He initially believes that Esther’s position as head of the PTA will let him get away with anything, only to find out how wrong he is. He sees firsthand how prejudiced Turkletaub is against Johnny, and how easily provoked he is. He and we see how Irving can be obnoxious, irritable, and even abusive (be warned that corporal punishment is depicted quite bluntly), but also loving, goofy, and driven by a genuine desire to see his son succeed – and his own awareness of how cruelly unfair life can be.

Even Aaron isn’t simply a lovable grandpa; he admits that putting Paul in the private school was his idea, and when Paul tells him about his schoolmates’ racism, Aaron urges him, with a few dollops of profanity, to stand up for the persecuted – to be a mensch.

Hopkins is naturally wonderful, but the more I think about it, the more I realize that Strong is the MVP. Gray’s script doesn’t always link the facets of Irving’s character smoothly, but Strong is as convincing in his moments of decency and humor as in those of rage (he’s truly frightening in the bathroom scene) and resignation. Hathaway is also quite good as the comparably complex Esther, though the film forgets about her somewhat towards the end.

Repeta and Webb are both quite good, despite some awkward line readings; Webb in particular finds the right mixture of youthful optimism and imagination, defiant anger, and a growing awareness of his own unhappy lot in life. Growing up, I knew kids like Johnny (and I wasn’t entirely unlike Paul, although I grew up a long, long way from New York), and there are scenes with them and between them that ring quite true indeed. But the whole cast is quite good, including Jessica Chastain in a surprise cameo.

The film suffers, like a lot of films in this genre, from a certain lack of narrative focus and a fragmentation which makes the individual scenes feel like isolated sketches; things happen and are rarely referenced again, even when you’d expect them to haunt the characters at least a little. And some of the characters, like Ted, play surprisingly little role in the story, given how close they are to Paul. But it’s still a very good film, well crafted, well observed, and extremely well acted. We’ll see if the awards groups take note.

Score: 85

Soft & Quiet (2022) – ***½

CW: racism, violence.

Soft & Quiet is a film of such raw, mounting intensity – what we see was played as a single take, although the finished film is edited together from several go-throughs – that in the moment you can easily forgive its shortcomings, and acknowledge after the fact that, as messy and heavy-handed as it can be, its best moments truly capture the chaos of unfettered hatred, and when the credits roll, you’re unlikely to be unshaken, though whether you’ll feel exploited by the film or galvanized by it is another matter entirely.

Although the film itself buries the lede somewhat (and if you can see it without knowing what it’s about, do so), it deals with the first meeting of a group calling themselves “Daughters of Aryan Unity,” comprising half a dozen women in a small town who share grievances about the supposed status of white people in modern America. For example, Marjorie (Eleanore Pienta) resents a co-worker for being promoted ahead of her, despite their being hired around the same time. And Kim (Dana Millican) is upset by the behavior of the non-white teenagers who come into her store.

The group is led by Emily (Stefanie Estes), a kindergarten teacher who’s introduced taking a pregnancy test (presumably negative), and whose attitude is established early on when she casts a sideways glance at a Latine janitor, then asks a student to request the janitor not mop the floors of the school until all the students have left. Emily tells her comrades they must be:

Soft on the outside, so vigorous ideas can be digested more easily. Now we are the best secret weapon that no one checks at the door, because we tread quietly.

And so, at first, it would seem that Emily and her friends aim to be stealthy in their bigotry. But after the meeting is forced to end early (they met in a church, and the pastor (?), presumably disturbed by what they’re discussing, tells them to go), they plan to decamp to Emily’s house…but then a chance confrontation with two Asian-American women Emily knows leads to an impromptu hate crime, which begins with no clear plan but devolves into harrowing brutality.

The meeting scene is probably the weakest in the film, because the character’s grievances feel too on-the-nose, too scripted; the actors do what they can to pull it off, but it feels just a touch too much like a dramatic reading of a comments section (and while a sick joke involving a pie makes for a memorable image, it also rings false). The scene also raises the question of why the group didn’t just meet at one of their homes, where their privacy would be assured – but let’s move on.

When the action shifts to Kim’s store and the fateful confrontation occurs, the film’s strengths and weaknesses alike come to the fore. You may wonder Lily (Cissy Ly) and Anne (Melissa Paulo) remain in the store when it’s clearly a hostile environment, and when the situation devolves into violence, the turbulent camerawork and shouted dialogue obscure at least one key story point: it would seem Emily’s brother is in prison and that she already knows Lily and/or Anne, but it’s a bit harder to parse than it needs to be.

On the other hand, we get a good look at the darker side of Leslie (Olivia Luccardi). We’ve already glimpsed the words liebe zu hassen on her jacket; they mean “love to hate.” And we’ve heard her say how she got involved with white supremacy in prison and how it gave her a sense of purpose and community. But now we see how ready she is to escalate any given situation, how quick she is to antagonize her supposed allies, and how completely amoral she is. Luccardi’s performance is, simply, the best part of the film; she’s terrifyingly convincing.

We also see how Emily treats her husband Craig (Jon Beavers), quietly mocking his masculinity, urging him to be “strong,” which in this case means abetting their felonious intentions; her friends likewise mock him for urging caution and restraint, equating, as bullies tend to do, standing up for oneself with doing exactly what they tell you to do.

And as the home invasion that begins as a hateful prank descends into a violent nightmare, we see not only how aimless and careless these supposed exemplars of white supremacy are, but how quickly they lose control of the situation when things don’t go as planned, how quickly they go for each other’s throats (with Leslie usually the first to lunge), and how frightened and confused they are when matters get too real, in contrast to how big of a game they talked beforehand.

The final movement of the film takes place mostly in the dark, with only the odd lamps, headlights, and last bits of twilight to help us see what’s going on at all; it’s a credit to writer-director Beth de Araújo that the tension is maintained fairly well, and that the final beat is sufficiently foreshadowed. Indeed, it’s de Araújo’s direction that ratchets up the tension so well to begin with, and if that helps to obscure the weaker elements of the script, it still makes for a viscerally upsetting 90 minutes.

de Araújo herself is of Chinese and Brazilian descent and has dual American and Brazilian citizenship. In dealing with this subject matter, she’s speaking from the heart, and she found a cast (Estes is a shade too studied at times, but has the right fanged sweetness and fragility for the character) and cinematographer (Greta Zozula certainly went the extra mile here) who brought her vision to unnerving life. It’s not a revelatory look at the face of modern racism, but as a portrait of these characters under these circumstances, it does pack a punch.

Score: 80

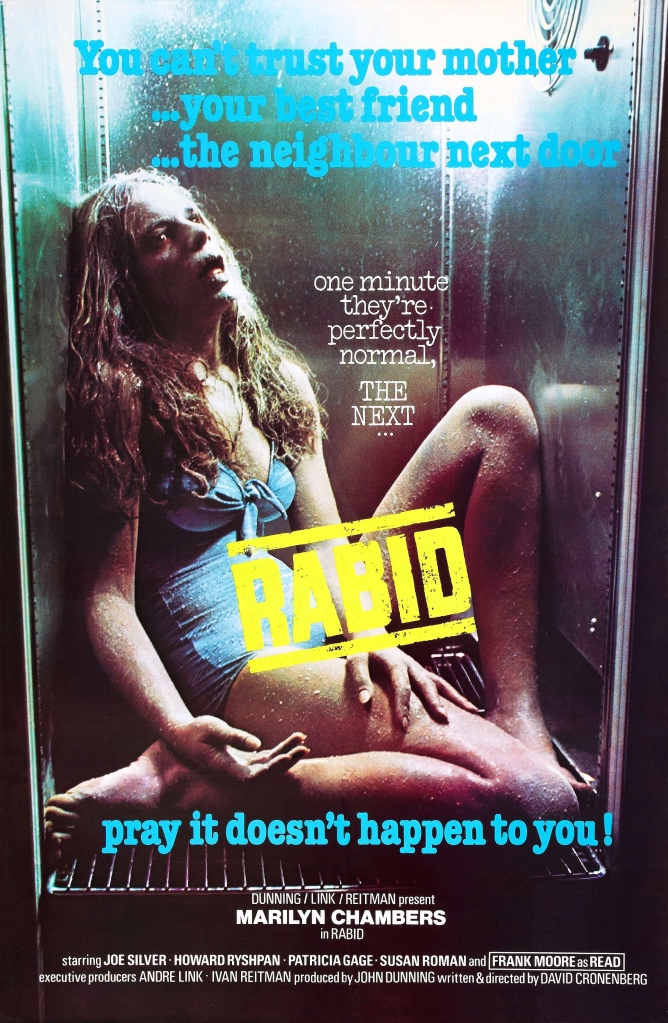

Rabid (1977) – ***

To a degree, Rabid feels like a remake, or perhaps a revision, of Cronenberg’s previous film, Shivers. Both deal with an epidemic caused by experimental science which drives the infected to prey upon others, with the efforts to control it, and with the human relationships that get caught up in the breakdown of the normal order. Both feature disturbing sexual overtones and body horror – Cronenberg’s trademarks. Both are also set in or near Montreal, and feature Joe Silver in a key supporting role as a voice of reason, or at least an emblem of common sense, who finally falls victim to the irrational plague.

But it’s also a very different film. It’s less viscerally upsetting – the violence is more fleeting, the sexuality is more symbolic, the body horror is more subtle. It has a much larger scope, thanks to a larger budget – where Shivers was mostly confined to a single high-rise, Rabid takes us across the countryside, through the streets of Montreal, onto the subway, and of course to the Keloid Clinic, a center for plastic surgery where all the trouble began.

It begins when Rose (Marilyn Chambers) is badly injured in a motorcycle accident while riding with her boyfriend Hart (Frank Moore). The Keloid Clinic is the nearest medical facility, and Dr. Keloid (Howard Ryshpan) uses a technique he’d developed to repair Rose’s internal injuries with skin grafts from her leg. She remains in a coma for a month, but abruptly awakens one night, and when another patient checks on her, she pulls them into an embrace – and a stinger emerges from an opening on her skin and sucks their blood.

That patient soon devolves into a literally bloodthirsty beast whose symptoms, including foaming at the mouth, resemble rabies. And they’re only the first, because Rose has infected others, who infect others, and so on. If not killed, they die in fairly short order, but Rose remains healthy; she just needs to feed on human blood, and only human blood. As martial law is imposed on Montreal to control the plague, we can only watch and wait as Rose infects more people and wonder when the truth about her will come out – and what this will mean for her and Hart, who doesn’t know the truth and just wants to get back to her.

The potential tragedy of Rose’s situation doesn’t fully come through, partly because Cronenberg’s script is pulled in too many directions, partly because he was still learning how to really introduce emotional complexity into his stories, and partly because Chambers’ performance isn’t quite up to par. She’s not terrible, and gamely plays her ample nude scenes (she was best known for her work in Golden Age porn), but her line deliveries tend to be somewhat stiff.

Aside from Silver, who plays Keloid’s business partner Murray Cypher with rumpled charisma, the performances are fairly unmemorable – more polished than those in Shivers, but not much more than functional. And, unfortunately, Cronenberg’s script is likewise more polished (for the most part – we never do learn just why Rose developed the stinger and I’m not sure if that was an oversight or what) but lacks the distinctive dialogue that marks most of his other work.

On the other hand, his direction takes a step up, with better-staged scenes and improved imagery; scenes like the attack of a plague victim on the Montreal subway are chaotic, but effectively so. René Verzier’s cinematography helps, showing off rural Quebec and 70s Montreal to similar advantage; much of the film is set against gray skies, at twilight, or at night, and the lights of cars and streetlamps glow beautifully. And the makeup effects, again supervised by Joe Blasco, are delightfully visceral, especially the faces of the infected with their pallid skin, foaming mouths, and oozing eyes.

One miscalculation was the use of a musical sting to mark Rose’s attacks; it’s the same sting used whenever nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition, and it’s hard not to giggle at a moment which should be horrifying. Comedy and horror do often go very well together (and the music supervisor was Ivan Reitman, who would later combine them with considerable success), but here it just feels silly.

What doesn’t feel silly are the scenes dealing with the response to the epidemic, with vaccine mandates, cards denoting one’s vaccinated status, checkpoints, and a general atmosphere of paranoia. It adds resonance to a film which has been a bit forgotten outside of its status as an early work of its director, and while it’s not as accomplished or impactful as his best work, it’s more than worth a look for genre fans.

Score: 72

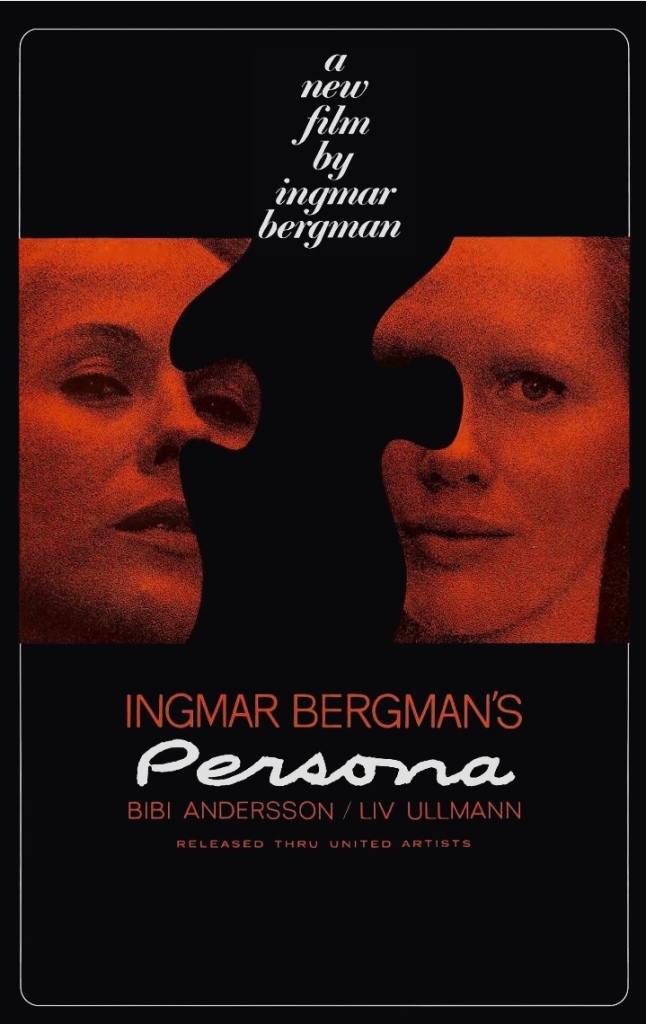

Persona (1966) – ****

“Persona has been for films critics and scholars what climbing Everest is for mountaineers: the ultimate professional challenge.” So Thomas Elsaesser wrote, and watching the film, especially for the first time, it certainly joins Last Year at Marienbad among the ranks of capital-A “Art Films.” It’s easy to mock such films for their obscure meanings, pervasive enigmas, and seeming self-seriousness – but to actually watch and analyze these films not only reminds us of the joys of interpretation but reveals how much fun they were to craft. Not in a sense of putting one over on the viewer; rather, in creating an accomplished work of art which also invites/demands conscious engagement and analysis. For my part, there’s nothing quite like having your work analyzed and interpreted by others; it brings the work to life in a most thrilling way. Bergman was only human, and I could certainly imagine he relished the feeling as well.

He also declined to explain Persona, overtly placing the burden of explanation upon the viewer. As such, I’ll offer my own thoughts, without trying to offer a comprehensive overview of the possible interpretations (which would take far too long).

For me, the film is a meditation on art, on being an artist, on creating art and reflecting oneself through the creation of art. From the opening shots of a film projector coming to life, bookended by the final shot in which it shuts down, from the prologue in which a universal film leader is intercut with strange and provocative images, including a briefly glimpsed erect penis and a bit of the silent slapstick homage from Bergman’s own The Devil’s Wanton, to the fleeting glimpse of the camera itself near the end (with Bergman’s director’s chair visible in a reflection), the film is deeply self-aware and self-referential.

But Bergman wasn’t just a filmmaker, he was a theater director, and it’s no coincidence that the film concerns Elisabet Vogler (Liv Ullmann), a stage actress who unaccountably stops speaking – and through the end of the film, unambiguously speaks only twice, once reflexively, once at the urging of her nurse, Alma (Bibi Andersson). Most of the film focuses on the time the two women spend at an isolated beach house, where Alma attempts to bring Elisabet out of her silence. It’s a theatrical set-up, and it’s worth noting the scene at the end where Alma puts away the outdoor furniture – like the striking of a stage set.

Then again, there’s dozens of images here worth noting and analyzing. During the prologue, we see Elisabet’s son (Jörgen Lindström) reaching for what seems to be a projected image of his mother (and/or Alma); is this commenting on how the children of actors must perceive their parents? Or how children perceive their parents in general? We also see a nail being pounded into the palm of a hand. Obviously, it’s a reference to crucifixion, but who is the Jesus in this scenario? Who are the Romans?

One scene which stood out to me also comes early on, when Elisabet is alone in her hospital room (that is, unobserved by any potential audience) and sees an act of self-immolation on television, which horrifies her. It’s mirrored by a much later scene, in which she examines the photograph of the Warsaw Ghetto being liquidated, noting the terror on the face of the young boy, and again being greatly shaken. Does this scene offer a possible explanation for Elisabet’s silence – her belief that art is irrelevant in the face of such genuine horrors, or incapable of explaining or preventing such suffering?

Before being sent to the beach house, Elisabet’s doctor (Margaretha Krook) describes her present silence as a performance, one she will give up eventually. It’s a well-considered observation, but if Elisabet ever does stop playing this role, we don’t see it, at least not unambiguously. And of course, one of the most famous scenes in the film involves a monologue in which Alma explains Elisabet’s internal conflicts over being a mother, describing her motives in having a son and her ongoing resentment of the boy. How would she know?

Everyone around Elisabet tries to understand her, tries to solve her, projects their own feeling onto her; it’s a prescient reflection of the parasocial relationships we have with celebrities, and it’s also simply a reflection of how we respond to works of art – including this film, which is so open to interpretation. There’s also the famous image in which the two women’s faces are merged, and a chord reverberates on the soundtrack; the image itself is rather unsettling, but is the chord a cheesy touch or another bit of self-reference – Bergman playing with a horror-film trope in a film which dances around being a horror film itself?

Beyond the interpretive dance one can do with this film, one can appreciate it as a masterful work of cinema. It’s magnificently performed by Andersson as the grounded, talkative, profoundly human Alma and Ullman as the detached, silent, profoundly enigmatic Elisabet, beautifully shot in black-and-white by Sven Nykvist – the close-ups are fantastically intense, and there’s a great tracking shot as Alma pursues Elisabet across the landscape – daringly scored by Lars Johan Werle, and of course superbly directed by Bergman himself.

It’s not a faultless film, and I don’t think all of Bergman’s experimental touches work equally well; he was trying a lot of new things here, and some stuck better than others. But it rests on the rock-solid core of a fascinating relationship between two women, and offers such a wealth of interpretive possibilities, that there’s no question of its greatness.

Score: 92

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022) – ***½

The death of Chadwick Boseman was one of the most unexpected losses in recent entertainment history, given how his career was thriving while his health was failing – a fact he kept secret from all but a trusted few. It’s only fitting that Wakanda Forever opens with the death and funeral of T’Challa, that the Marvel logo be composed of clips of Boseman’s performances as the character, and that the film as a whole be informed by loss, grief, and the confusion and instability they so often give rise to. It’s a somber film in which even triumphant moments are shadowed by sad truths.

That Wakanda Forever falls short of the high bar its predecessor set (I think it’s pretty easily the best MCU film to date) is unsurprising, nor is it terribly surprising why: it functions where the first film soared, embodies competence instead of inspiration, hits the beats it needs but doesn’t resonate like that film did. But is it because the film was hamstrung by the loss of its intended star, or because it has to function as more than a story of Wakanda coming to grips with losing him?

Princess Shuri (Letitia Wright) is haunted by T’Challa’s death and blames herself, given that she was attempting to treat him at the time of his death. Their mother, Queen Ramonda (Angela Bassett) tries to help her process her feelings, but has a good deal more on her plate; after T’Challa revealed the true wealth and power of Wakanda to the world, other nations have been trying to get their hands on vibranium, with some hiring mercenaries whom Ramonda ceremoniously leaves kneeling in front of the UN General Assembly.

Elsewhere, a machine to detect vibranium has been deployed on the ocean floor, but shortly after finding a deposit, the operation (an American operation) is attacked by forces led by Namor (Tenoch Huerta Mejía), the king of the undersea nation Talokan. He’s determined to find whoever developed the detector, and when word of the device reaches Wakanda, Shuri and Okoye (Danai Gurira) go to the MIT campus to get to Riri Williams (Dominique Thorne) first.

Riri, a brilliant inventor, has not only developed a vibranium detector, but an Iron Man-esque suit as well, and uses it when the FBI comes calling – but after successfully evading the Feds, Namor’s forces intercept them, abducting Shuri and Riri and leaving Okoye to explain herself to Ramonda, who strips Okoye of her rank. She turns to Nakia (Lupita Nyong’o), who has been living a quiet life in Haiti, to rescue them.

Namor tells Shuri about how his people fled conquistadors centuries earlier, and how he will defend Talokan against outside incursion. He wants Wakanda to stand with him against colonization, but warns that he will easily defeat them should they oppose him. Shuri is aghast at his intentions, and after Nakia rescues her and Riri and returns them to Wakanda (killing two of Namor’s guards in the process), Namor and his forces attack Wakanda, strengthening Shuri’s resolve to destroy him at any cost.

Given the length and scale of the film, I’ll stop there; suffice to say, there’s a climactic battle, additional tragedy, and plenty of doors opened for the future of this franchise. There’s even a modest surprise or two.

There are also ties to other Marvel properties, namely the upcoming series Ironheart (Riri’s superhero identity) and the character of CIA director Valentina Allegra de Fontaine (Julia Louis-Dreyfus), who appeared at the very end of Black Widow and has apparently appeared/will appear in the series The Falcon and the Winter Soldier and Thunderbolts. She’s also the ex-wife of Everett K. Ross (Martin Freeman), for what that’s worth. (It might to serious Marvel fans, but I haven’t delved into the series and have no plans to.)

These are some of the weakest elements of the film, and if Riri is to be the protagonist of an entire series, I hope she’s given more to work with; here, she’s a pretty generic prodigy who makes a few forgettable quips, and Thorne’s performance doesn’t exactly elevate the material. Ross himself is saddled with a full subplot when all he really needed to do was point Shuri and Okoye to Riri; it seems like he’s being set up for future plotlines as well, but it’s hard to get excited about them.

More interesting are what will become of Shuri, who’s going to be guiding Wakanda into an increasingly uncertain future, and what role M’Baku (Winston Duke) might play in that future; he’s a good and honorable character, but there’s the distinct possibility he’ll have more power down the line. (In the comics, he’s a supervillain named Man-Ape; I’m not sure how much of that material Marvel might be willing to use, but we’ll see.)

If the first film offered a truly great ensemble, this one offers a solid one; Gurira, Bassett, and Duke are very good, Wright is solid, and Mejía is a fairly good antagonist, at least as MCU antagonists go. Everyone else is fine, while the sets and costumes are better than fine (I do wish we got to see more of Talokan), the action scenes, despite what I’d read, are perfectly adequate (if never galvanizing), the score adds some nifty new themes, and the visual effects are as good as you’d hope. The sound mixing seems a bit iffy at times, but maybe it’s just my hearing.

It’s just hard to rave about any of it, and I don’t if it would grow on me like the first film did, or if that film just caught lightning in a bottle. Ryan Coogler did a good job in the face of a trying situation and paid moving tribute to his fallen star. But I think of the scene in the first film, the scene where T’Challa and Killmonger first face off, and how the raw pain and emotion of that scene really haunted me. I don’t think anything here will.

Score: 82

I shudder at the idea of lumping ROMA (a work of far-reaching social vision and breathtaking artistry in which two mature women are the writer/director’s focus while the young child characters who presumably come-of-age don’t register in my memory at all and I don’t think were intended to) in with the likes of LADY BIRD (about the painful teenage narcissism and entitlement of a girl whose personality made me wish the film had been about Feldstein’s character instead and whose mother seemingly has the patience of a saint). Not the same thing at all.

…I honestly liked Lady Bird more.

But I probably should watch Roma again. I thought it was very good (high ***.5), but I didn’t find it, as you put it, breathtaking.

I think it’s interesting and unexpected that I’ve given ROMA three viewings now and have liked each one a little more than the last, even with being lucky enough to start off in a cinema (one that no longer exists, sigh).

LADY BIRD actually hit quite strongly on my way out of the theatre but was starting to fade even before the night was over, and then I couldn’t even get through a later attempted re-watch.

I’ve liked a number of James Gray works, but I can’t get past how pedestrian the trailer for this new one makes it look.

I’ll just add that BELFAST did fall away slightly for me upon a revisit, after initially leaving me with a feeling of true greatness. (Ugh, hate when that happens.) Also that I’m unsure right now whether MINARI will even get a rewatch from me; I’m currently kind-of inclined to be satisfied with my broadly-positive-though-not-passionately-adoring response.