The Phantom of the Opera (1925) – ***½

One of the most famous of all silent horror films, and arguably the true starting point of Universal horror (depending on how you classify 1923’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame), this particular version of The Phantom is hard to critique because of its own fractious history. In brief, the film had a troubled production thanks to director Rupert Julian alienating nearly everyone on the set, with star Lon Chaney effectively directing his own scenes. Then, when the film premiered in Los Angeles in January 1925, it was poorly received, leading Universal to rework it extensively before an exclusive run in San Francisco that April. That too was not well received, leading to further reworking before the New York premiere in September. The reviews were mixed, but the film was a massive hit.

Then, in 1929, the film was reworked once again, this time to make it a sound film, and while the soundtrack survives, most of the new footage (reputedly over half the film was reshot) is lost. However, around this time a high-quality print was made, using mostly 1925 footage but edited to accommodate (more or less) the new soundtrack. This version was preserved by the George Eastman House, while the 1925 version of the film was preserved only in lower quality prints.

In 1996, a restoration was carried out which took the George Eastman House print, restored the original color tinting and the Bal Masque sequence in two-strip Technicolor, and added a new score by Carl Davis (whom I saw conduct his score for Abel Gance’s Napoleon when that was shown in Oakland in 2012). That’s the version I watched, then watched again with a commentary track by Scott MacQueen, who needles Julian’s shortcomings as a director and details the film’s tumultuous history.

The basic story, of course, deals with Erik (Chaney), a disfigured man who lives beneath the Paris Opera house and has, from the shadows, managed the career of soprano Christine Daaé (Mary Philbin), who is being romanced by Raoul de Chagny (Norman Kerry). Erik has threatened the managers of the Opera should Christine be replaced in the role of Marguerite in Faust, and when they defy him, he brings down a chandelier, luring Christine away in the chaos.

He takes her to his underground home, revealing his obsessive passion for her. She unmasks him and is horrified by his face. He allows her to return to the surface to sing Marguerite once more, and during a masked ball, she begs Raoul to save her from the Phantom. Overhearing them, the Phantom kidnaps her during the performance, and Raoul gives chase with the help of Ledoux (Arthur Edmund Carewe), a Parisian detective who’s been pursuing the Phantom.

Meanwhile, an angry mob, led by Simon Buquet (Gibson Gowland), whose brother was killed by Erik, charges into the catacombs as well. After torturing Raoul and Ledoux, Erik drags Christine to a carriage and tries to escape. She throws herself out, causing Erik to crash. He flees from the mob as Raoul and Christine embrace, and is finally beaten and thrown into the Seine to drown.

Of course, originally Erik was to be morally redeemed and, after letting Raoul and Christine leave, die of a broken heart. And Ledoux was originally “the Persian,” who knew Erik as chief torturer to the Shah. And while Erik was deformed at birth in the novel and the print I watched, at one point, he was to have been deformed by being buried up to his neck in an anthill! That’s just a taste of how much this Phantom changed before assuming the form I watched. But if the finished product is good, that can be overlooked.

And it is good, if not great. It’s not great, partly because, as MacQueen points out, Julian wasn’t a very good director and much of the film is simply not that memorable. The sets and costumes are first-rate (the Opera House set stood for 90 years before being mostly dismantled), and between the color tints and use of early Technicolor, it’s consistently handsome to look at.

But outside of the best scenes, it’s rarely engaging. Look at 1928’s The Man Who Laughs, a film similar in so many ways, but so much better in part because it had one very skilled director (Paul Leni), who brought a real vision to the table and was able to execute it without pissing off everyone around him. The camerawork in particular is so much more vivid and fluid than Julian’s generally static compositions here.

The best scenes, unsurprisingly, are those Chaney reputedly managed himself, and they highlight his vivid, emotive performance and justly celebrated makeup. Philbin is daintily pure and Kerry has a noble moustache, but they’re unable to get much from their dull characters. No one else, save perhaps Carewe (who’s at least allowed to be mysterious until his identity is revealed) and Snitz Edwards as a comic-relief stagehand, are much more than figures on the screen.

The story and the spectacle are enough to keep it watchable even when Chaney isn’t around, but it’s only when he assumes center stage that the film really lives up to its reputation. He may have hated the changed ending, but his final flourish, bluffing the bloodthirsty mob with an empty hand before revealing the trick with a laugh, is the stuff of legend.

Score: 81

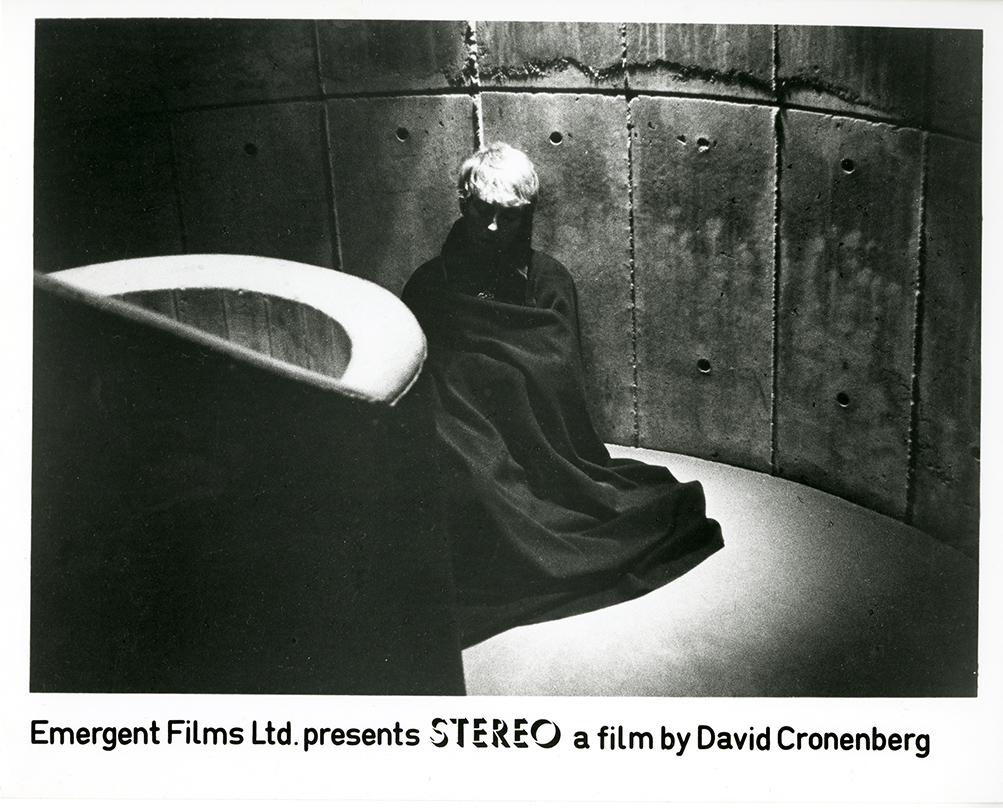

Stereo (1969) – **½

The full title is Stereo (Tile 3B of a CAEE Educational Mosaic).

David Cronenberg’s first feature was this hour-long quasi-documentary about an experiment to bring out the telepathic abilities of human beings. A group of young people underwent surgery to remove the speech centers of their brains and were then sent to live together at a facility of the Canadian Academy for Erotic Enquiry, where they were encouraged to form personal bonds – including sexual relationships, stimulated by the use of aphrodisiacs. The potential ramifications for sensory perception when extra-sensory perception is introduced into the equation are touched upon, but the format of the film doesn’t really allow for a full exploration of this.

The camera Cronenberg used made too much noise, so the film was shot silent, and aside from the dryly delivered, heavily technical narration, the film is wholly silent – there’s no score, no sound effects, no nothing. And the images only sporadically align with the narration, or at least appear to; it’s the kind of film you can imagine making sense to its makers, but it falls short with the casual viewer.

Cronenberg fans will find a lot to appreciate, however. Shot in crisp black-and-white throughout the Andrews Building on the Scarborough campus of the University of Toronto, Cronenberg makes the most of the building’s Brutalist architecture, its rigidly patterned interiors and narrow hallways. Acting as his own cinematographer, he takes obvious delight in moving his actors around the dramatic shapes of the building and playing off the building’s own geometry with the visual geometry of his compositions.

And his script shows the seeds of the ideas which he has returned to throughout his career: the attempts of science to expand the boundaries of human nature and control the flow of evolution, the intersection of science and humanity, the interplay of science and sex, and, of course, unintended consequences. But he would integrate those themes far more successfully into his later works, not least because he would be able to develop actual characters to explore them through.

Here, however, we have only the nameless young people, the subjects of the experiment (which ties into the work of one Luther Stringfellow, who is never seen), and aside from one young man, played by Ronald Mlodzik (who’d appear in several other early Cronenberg films), we never really feel any connection to them. One of them seems to be a handler and chases Mlodzik at one point. Two of them are female (Clara Mayer and Arlene Mlodzik), and Mayer has several topless scenes, while Mlodzik wears some revealing costumes.

That last bit ties into the sexual themes running through the film – which very much mark it as a product of the late 60s – with the narration suggesting that contrary to the heteronormative values of present society, the optimal orientation is a kind of omnisexuality, and while the homosexual elements are portrayed with greater restraint than the heterosexual scenes, they’re certainly present. You have to wonder how much the University knew about the film’s content.

Again, though, because we really don’t know who these people are, and because the narration is sporadic and makes little attempt at establishing a clear narrative or even temporal framework, we never get truly invested in what’s happening. As such, despite the film’s brevity, it gets a bit dull after a while, and as much as I appreciate Cronenberg’s imagery, his pseudo-academic dialogue (“experiential space continua”), and his stylistic touches like the use of slow-motion, I found myself getting a bit drowsy before it was over.

Score: 62

Crimes of the Future (1970) – **½

If Stereo made me drowsy, Crimes all but put me to sleep – yeah, it had been a long day, but that’s still never a good sign. When I went back the following day and gave most of it a proper viewing, I saw it through to the end easily enough. But whether you’re drifting or fully alert, I can’t really recommend this particular Crimes unless you’re trying to see everything Cronenberg ever made. Obviously, his most recent film of the same title is far, far better, but while it’s not a remake of this film by any means, they do have a few common elements, most notably the mysterious new organs one character is growing as a form of “creative cancer,” but also the troubling role played by children in the narrative and the presence of shadowy Powers That Be.

This film follows the character of Adrian Tripod (Ronald Mlodzik again), director of the House of Skin, a dermatological institute formerly led by his mentor, the supposedly late Antoine Rouge. Rouge discovered a disease, known as “Rouge’s Malady,” which has caused the deaths of many women – and reputedly caused his own. The disease also causes its victims to secrete a substance known as “Rouge’s Foam,” which is eaten on multiple occasions in the film.

Tripod is also involved with the Oceanic Podiatry Group, performing and receiving foot massages on their campus, with Metaphysical Import-Export, bringing various men bags of what appear to be women’s undergarments, which they sort into smaller bags, and with a conspiracy that aims to preserve the human race through very troubling means.

This is all to say that Crimes has marginally more plot than Stereo and has at least one named character (and several reasonably identifiable unnamed characters). It was also shot in color, and while it also had to be shot silently (Tripod’s narration pervades the film), it breaks up the silences on the soundtrack with sounds that might be bird calls, electronic hums, machine noises, falling rain, and so on, but are never clearly one thing or the other.

It’s still slowly paced, frequently opaque – there’s an implied assassination near the end which I can’t even begin to explain – lacks any emotional pull and offers precious little food for thought. There is the question of what the stereoscopic pictures are (I’d assume pornography), and there is the theme of disease as a way of life – that and the mention of skin diseases caused by cosmetics brings Todd Haynes’ Safe to mind. And there’s also the question of whether or not Tripod is Rouge, which seems quite possible, but it’s also hard to really care.

As with Stereo, the real value here is in seeing a great auteur finding his feet. As a director, he was already doing fairly well, again finding striking Brutalist locations (the Ontario Science Centre in Toronto is heavily featured), smartly framing his shots, using light and color well (the scene where the conspirators meet looks especially cool), and achieving an unsettling atmosphere throughout, whether in scenes which are indisputably strange and off-putting, or scenes which simply focus on Mlodzik’s piercing stare and permanent sneer (you can see why Cronenberg liked working with him).

But as a writer, he was still caught up in his ideas and still struggling to wed them to a compelling story. In showing us the world as seen by Adrian Tripod/Antoine Rouge, he displays considerable imagination and pulls off a few sickly amusing turns of phrase, which Mlodzik’s mannered narration does justice to. But all of this would’ve worked better at half or one-third the length; even at 63 minutes, it really drags. I’m glad to have seen it, but once is probably enough.

Score: 63

You know what time it is? Time for some more shorts!

- Transfer (1966) – Cronenberg’s very first film, this surreal comedy depicts a session between a therapist who’s fled to the snowy wilderness (Mort Ritts, who looks kind of like Warren Oates) and his nebbishy, persistent patient Ralph (Rafe Macpherson). There are frequent visual non sequiturs, shifts of settings, parodies of psychological jargon, and bits of outright absurdism, from Ralph’s outfit (half 20s college football fan, half thermal underwear) to the opening image of the therapist dipping his toothbrush in grape soda (!). It’s pretty crude, but in a likable way – Ritts and Macpherson are clearly reciting memorized dialogue, but they seem enthusiastic about the task. Not a very characteristic work, but whatever. Score: 66 – ***

- From the Drain (1967) – Next, Cronenberg made this short about two men (Ritts and Stephen Nosko) sitting in a bathtub. Ritts does most of the talking, at first seemingly trying to pick Nosko up, then suggesting they’re members of a veterans’ organization. Nosko warns him about a tendril that emerges from the drain and kills people. Ritts laughs this off, then tricks Nosko into being strangled by the tendril – and we learn he wasn’t its first victim. Here Cronenberg first dips his feet into horror, albeit with the most primitive special effects (the tendril is basically just green string); more interesting is dissonant use of harpsichord music on the soundtrack. Still a minor work by a filmmaker learning his craft, and I’m not wild about Ritts’ prissy performance, but it shows the promise he would amply deliver on. Score: 65 – ***

- Pink Komkommer (1991*) – While making a pot of a tea, a woman has several dreams, which have the same soundtrack (a series of sound effects and vocalizations) and are grotesquely erotic. This allows it to showcase the work of multiple animators, including Sara Petty (whose work I’ve praised elsewhere) and Marv Newland (of Bambi vs. Godzilla fame). Petty’s semi-abstract sequence is probably the best and most artful, though I appreciated Craig Bartlett’s claymation and Janet Perlman’s mime-narrated sequence as well. Overall, though, it wears thin pretty quickly, with too many segments being simply gross and childish. (*Copyrighted 1990.) Score: 59 – **½

- Wet Blanket Policy (1948) – This is the only short film to date nominated for Best Song (or, to my knowledge, any feature-film category), for “The Woody Woodpecker Song,” a very catchy little tune punctuated by Woody’s trademark “oh-ho-ho-HO-ho.” Oddly, it wasn’t nominated for Best Animated Short (and Walter Lantz never did win a competitive Oscar). Not that it needed to be, but it’s a fun little piece in which Woody must outwit shady insurance salesman Buzz Buzzard (voiced by the great Lionel Stander), who takes out a life insurance policy on Woody – and promptly tries to collect on it. The usual cartoon shenanigans ensue, including what might be an homage to Charlotte Perkins Gilman. I can’t say Woody’s ever been a favorite character of mine, but it’s cute. Score: 74 – ***

- Duck Amuck (1953) – I decided to rewatch and review the three Chuck Jones cartoons Roger Ebert chose to represent his illustrious career. First is the madcap post-modernist struggle of Daffy Duck against an animator who won’t play ball, depriving Daffy of scenery, stability, and even sound before the great final reveal. It’s probably my dad’s favorite WB cartoon, which is fitting since it’s so reminiscent of Sherlock Jr., probably his favorite Keaton film. For me, it’s lost just a bit of its freshness, but the way it gleefully plays with form – especially with sound – remains delightful. Score: 87 – ****

- One Froggy Evening (1955) – Then there’s the story of Michigan J. Frog, who sings and dances only for the workman who found him, thwarting the latter’s attempts to exploit his inexplicable skills. As a kid, I found it all a bit frustrating – why didn’t the damn frog sing for anyone else? – but now I find the central theme of trying to bottle a miracle resonates as much as the workman’s struggles ruefully amuse. And Michigan himself is simply a great character with an impressive repertoire (pity “The Michigan Rag” wasn’t nominated for Best Song). Score: 89 – ****

- What’s Opera, Doc? (1957) – Finally, there’s this travesty of Wagner, combining elements of Der Ring and Tannhäuser and filtering them through the eternal struggle of Bugs and Elmer. I remember finding this a letdown, especially compared to its lofty reputation, and I still don’t quite love it (it’s the lyrics, I think). But I do appreciate it a great deal more, especially Maurice Noble’s stark backgrounds, Milt Franklyn’s magnificent arrangements (kudos for using the Tannhäuser overture, one of my favorite bits of Wagner), and the daring ending, not just the lampshaded tragedy but the omission of the traditional musical outro. Score: 86 – ***½

Don’t Look Now (1973) – ****

The most praised sequence in Don’t Look Now is probably the love-making scene between John (Donald Sutherland) and Laura Baxter (Julie Christie), which famously cuts between the act and the aftermath, as they get dressed, here resuming the appearance of a smart upper-middle class couple, there rolling about in naked abandon. It’s a justly celebrated moment, but I was also impressed by the scene prior, where Laura sits in the bathtub, unassumingly naked – no censorious bubbles here – and John brushes his teeth and weighs himself, likewise completely bare. It’s so rare, or feels like it, to see human beings so exposed yet so at ease.

And, on the subject of the film’s editing, I found the climactic scene just as virtuosic, as John rushes after the red-coated figure he’s glimpsed before, wondering if it really is the ghost of his late daughter, as Laura heads to meet him, then rushes after him desperately, and then as John finally comes face to face with the figure and learns the horrible truth, with the events of the film flashing before his eyes and ours as the pieces of the story fall tragically into place. It’s at once suspenseful and dreadful, impressing upon us a sense of inexorable fate.

The revelation that the figure is a diminutive adult woman has been criticized; Ebert called it “arbitrary and perhaps unnecessary.” But the original short story by Daphne du Maurier acknowledges this, with John’s final thought being “what a bloody silly way to die.” And to me, it works perfectly well because what would work better? It’s been established that there’s a serial killer in Venice – at least two bodies are found in the course of the film – and John must die at the end of the film, because he has already had a vision of his own funeral.

Really, a better title might have been If Only, because that seems to be the refrain of the story. If only John and Laura had watched their daughter more carefully, she might not have died. If only John had been more receptive to the notion of second sight, he might have listened to the warning that his life was in danger as long as he stayed in Venice. If only John had returned to England with Laura to check on their son (who was in a minor accident at school), he might have lived. Or if only he had waited in this place or that one for Laura when she returned, instead of rushing off after the red-coated figure by himself. If only, if only, if only.

Most of the film is set in Venice in the winter, when there are few tourists, and the city is cold and gray and empty. On one level, this adds to the film’s foreboding atmosphere. On another, it underscores how John is where he should not be. This is reinforced repeatedly throughout the film, by the Baxters’ largely empty hotel preparing to close, by the decision not to subtitle or otherwise translate the Italian dialogue, and by Bishop Barbarrigo (Massimo Serato) telling John he should’ve left with Laura – shortly before John is nearly killed in an accident. But he does not heed the warnings, and only realizes his own capacity for premonition when it’s too late.

The film plays with time, most visibly through its editing, but more subtly through John’s occupation as a restorer of medieval churches. At one point, he notes how Barbarrigo seems indifferent to the project, which to me underscores Barbarrigo’s pragmatism, just as John’s desperate assertion that their daughter is dead, in response to Laura relaying a psychic’s claim that her ghost was with them, underscores the irony of his situation.

It can’t have been a coincidence that, after his near-fatal accident, John and Barbarrigo walk by a poster for a Charlie Chaplin film – Marx wrote that history repeats itself, first as tragedy, then as farce, and while John’s story is a tragic one…well, “what a bloody silly way to die.”

There’s so much to break down on the thematic level that it’s easy to overlook the film’s dramatic qualities – and indeed, I’ll probably need another viewing to fully appreciate them myself. But it’s obviously a masterfully crafted film, with Anthony Richmond’s cinematography (influenced, I’m sure, by director Nicolas Roeg’s background as a cinematographer) creating a succession of haunting images, from the wine spilling on the photograph in the opening scene to the swirling fog in the climax, while Graeme Clifford’s editing is, as noted, quite brilliant. Pino Donaggio’s score is comparably strong, emphasizing the tragic and romantic elements of the material.

Sutherland is ideally cast as a man who does not grasp how outmatched he is by reality. His wide-eyed stare, lean features, and offbeat appearance (oh, the days when leading men could look so…human), especially the incredibly 70s moustache he wears, help to subvert the masculinity and authority he tries to project. Christie never reduces Laura to grief, fear, or a fanatical embrace of the supernatural, playing her simply as a human being in extraordinary – and extraordinarily trying – circumstances. And as the English sisters the Baxters meet, Hilary Mason as the blind, psychic Heather and Clelia Matania as Wendy are the quintessential middle-class English ladies of a certain age, as happy to discuss old family photos as to conduct a seance.

Indeed, one of the refreshing things about Don’t Look Now is how much the characters care about one another. There’s never a question that the Baxters are a devoted couple; neither their arguments nor their griefs undermine their union. Heather and Wendy’s sororal bond is rock-solid, and near the end John is quite happy to walk Heather back to their hotel. Barbarrigo is never less than a friend to John. And at the end, he approaches the figure with kindness, saying “I’m a friend.” Too bad the feeling wasn’t mutual.

Score: 91

Tár (2022) – ****

Tár deals with cancel culture the way Lydia Tár (Cate Blanchett) deals with just about everything that isn’t music, which is to say it glides past it, glancing only long enough to validate its decision not to, as Tár puts it, “get involved in intrigues.” That isn’t to say that the film itself validates or excuses Tár’s behavior, which in any case is left mostly to our interpretation. What the film is doing is telling us the truth about her, and the truth is that making music is the only thing that truly matters to her. Everything else can be sacrificed, not without regrets – this is too intelligent a film to deny its protagonist the full measure of her humanity – but with the sheer determination that got her as far as she’s gotten at the start of the film. By the end, however much she’s fallen from grace, she hasn’t given up.

But getting to that point is a long, carefully paced journey, one which is bold enough to run most of the credits at the start, over an overture whose relevance is only clear when all is said and done, one which asks us to be patient as it foregrounds long scenes, some of them lengthy single takes, many of them steeped in musical shop talk, and most of them focusing on Tár’s work as a conductor and a composer, with the thornier aspects of the story gradually creeping in as the pace quickens, until the final brisk movement which breezes through scenes which a more conventional film would have dwelled upon, then keeps going, threatening to confound us, until it ends, in its odd way, right where it should.

We meet Tár as a celebrity in the musical world, her curriculum vitae being recited at length by Adam Gopnik (playing himself) as he introduces her at an event promoting the pending publication of her autobiography. Later, she’ll return to her home in Berlin, where she’s chief conductor of the Philharmonic, and where she lives with her wife, concertmaster Sharon (Nina Hoss), and their daughter Petra (Mila Bogojevic). But she divides most of her day between the concert hall, attended to by her assistant Francesca (Noémie Merlant), and an apartment she uses for composition. Music has a way of coming first.

Her strength of will and opinion is established when she visits a conducting class at Julliard, butting heads with student Max (Zethphan Smith-Gneist) when he dismisses Bach for being a cis white male. You might expect this to come back to haunt her – but be patient. She learns that Petra is having trouble with a classmate. She confronts the child in question and says she’ll “get” her if she doesn’t leave Petra alone. You might expect this to bite her in the ass – but be patient. She also decides to replace her assistant conductor Sebastian (Allan Corduner), who takes it poorly, and takes an interest in new cellist Olga (Sophie Kauer), which everyone in the orchestra notices. How will either of these developments pay off? Take the journey and see.

What really brings Tár’s world crashing down is something we never learn the full truth about. We know one of her former proteges (who remained close with Francesca) lost her favor, and we learn that Tár discouraged her colleagues from hiring her. When she dies, Tár asks Francesca to delete all her emails. No sense getting involved in intrigues. This, of course, will backfire tremendously – but we never do learn just what happened between her and Tár. But we do learn that Tár uses people. And when they are not useful, she has no time for them. And soon the world that once worshipped her has no time for Tár.

But as I noted, by this point, the film’s paced has accelerated such that we are told less and less and must infer more and more. And while there are a few frustrating lacunae in the film, especially in the final third, by and large we know what we need to know, which is that Tár needs music more than anything. Power, position, love, friendships – the loss of these can be borne, as long as the music remains.

Todd Field’s script, like his direction, is subtle, thoughtful, and well-researched. I found its portrait of the musical world wholly convincing, which may not say much since I am no kind of musician – but everything in the film rang true, and I can’t ask for more. It’s hard to find any fault in the studied cinematography (maybe the dream sequences don’t quite land, but that’s it), the carefully controlled editing (it’s 158 minutes and not brisk, but it never drags), or the production design (the Brutalist apartment Tár and Sharon share is magnificently off-putting).

I have to praise the sound, which soars in the orchestra sequences and, in the quieter scenes, deftly introduces the distant sounds which haunt Tár, waking her in the night, disturbing her during a jog, or finding their way into her compositions. It’s hard to comment on Hildur Guðnadóttir’s score, most of which is apparently very subtle, but the classical selections we hear are certainly tremendous, even if we rarely hear more than a few notes at a time.

The whole cast is solid, with Merlant especially solid as the assistant struggling under her boss’ crumbling command, while Hoss is by turns quietly supportive and coldly devastated as Sharon, Julian Glover steals his scenes as Tár’s predecessor, and Mark Strong plays well against type as a nebbishy colleague/rival of Tár’s.

But this is Blanchett’s show, and what can be said except that she’s convincing at every turn, showing us Tár’s confidence and command while weaving in notes of insecurity, vulnerability, and arrogance. It would’ve been easy to make Tár the classical equivalent of Whiplash‘s Terence Fletcher, but as viscerally effective as that film was, this is going for something much defter, more thought-provoking, right up to that final line:

“Let no one judge you.”

Score: 90

2 Comments Add yours