Béla Tarr’s Satantango begins with a kind of visual overture, as we see a herd of cows wandering through a run-down, seemingly abandoned village, with a few attempts at mating, much mooing, and a general concerted movement to an uncertain destination. This is all depicted in a single lengthy take, with the camera moving along, not exactly following the cattle so much as moving through the village and rediscovering them as it trundles along. After around eight minutes, we fade out and the credits start to roll.

I use the word “overture” because it encapsulates many of Tarr’s visual and narrative themes (the latter somewhat more figuratively), themes he deploys again and again throughout the notorious 439-minute running time. On a technical level, you’ve got the use of lengthy takes with gradual, graceful camera movement, on a visual level you have the motifs of decaying buildings and muddy landscapes, and on a figurative level you have the cows, who here behave much like the human characters later will: wandering aimlessly through life (at least until they’re directed by someone who treats them like cattle), making noise, and engaging in purely carnal sex.

I’ve seen Satantango twice now, once in 2013, spread over three nights, on the infamously lacking Facets DVD, and once this week, all in one day (it was my day off and the weather sucked), on the fine new Blu-Ray from Arbelos Films. A decent amount of the film stuck with me, although several plot points were clearer this time around, in part thanks to some reading up on the film’s story and themes. To be sure, it’s a film more concerned with mood and atmosphere than narrative cohesion, but it’s not too hard to piece together what isn’t spelled out.

The challenges to the viewer are in accessing the film in the first place (hopefully that’ll be a bit easier now), in making the time to watch it, and in enduring the meticulous pacing. Not that the film is always painstakingly slow; much of it is relatively lively, if not brisk by any standard. But just when you think the pace is picking up, Tarr drops another long take, perhaps a slow pan around a room of sleeping drunks or a long trudge along a dirt road, to remind you of the kind of film you’re watching. (Another challenge, especially to some viewers, will be the depiction of animal cruelty, although Tarr has claimed that no actual harm came to the animal in question.)

I suppose a word on the story is necessary. It’s mostly set in and around a rundown agricultural commune in Hungary, either in the late Communist or early post-Communist period; it’s never really clear, but it doesn’t really matter. The members of the commune are waiting on their annual salary, and a few members are plotting to take all the money for themselves and abscond. But then word comes that Irimias (Mihály Víg), a member of the commune who disappeared and was presumed dead, is returning. Irimias, we learn, has his own plans to cheat the members, which may include delivering them into the hands of the authorities. And as amoral as they may be, they’re no match for Irimias; as one character says, “he could turn cow shit into a castle, if he wanted to.”

The first 260 minutes of the film mainly detail the events of a single day, beginning as Futaki (Miklós Székely B.) is awakened at dawn by mysterious bells, taking us through his discovery of the plot, the revelation of Irimias’ return, Irimias’ own plans and journey towards the commune, the drunken revels of the commune members, the observations of the drunken doctor (Peter Berling) who keeps extensive journals on his neighbors, and the strange behavior of Estike (Erika Bók), a little girl who is tricked out of her money, abuses and finally poisons her cat, watches the adults as they dance, approaches the doctor for help and runs away when he yells at her, and finally consumes poison herself in the ruins of a church.

The film, as many others have noted, has a tango-like structure, moving backwards and forwards in time, depicting the same events multiple times from multiple perspectives; for example, we first see Futaki looking out the window at dawn, then later we see the doctor watching him and drawing his own conclusions about what is happening. And we see the drunken dance first from Estike’s perspective as she watches from outside, and then again from inside, as the members of the commune dance, sway, play, or in one case wander around with a breadstick balanced on their forehead. (It’s such a drunk-person thing to do.) And of course, these scenes go on for minutes on end.

It’s in the final three hours when Irimias arrives and swings his plan into action; he may not have caused Estike’s death, but he certainly capitalizes on it, manipulating the members’ guilt and fear of police investigation, and they hand over all their money without a word. He sends them to a nearby manor, telling them he’ll see them the following morning at 6 (he tells them his plan is to set up a new communal farm), and goes off to arrange the purchase of explosives, but only after falling to his knees in front of the ruins were Estike died. Giving thanks for her fortuitous death? Perhaps.

While Irimias arranges to buy explosives – my guess is so he can frame the members of the commune as potential threats, but his reasons are left unexplained – the members make their way to the manor and camp out in its drafty ruins. In the morning, Irimias doesn’t show up on time, and they grow angry, realizing they’ve been duped. They start to fight, and Irimias – the cunning bastard – shows up, chastising them for being faithless and greedy. One of them wants his money back, and Irimias hands it over…but is able to shame him (with the help of his own wife and the member who wanted to rob his neighbors in the first place!) into giving it back. He’s just the sleaziest.

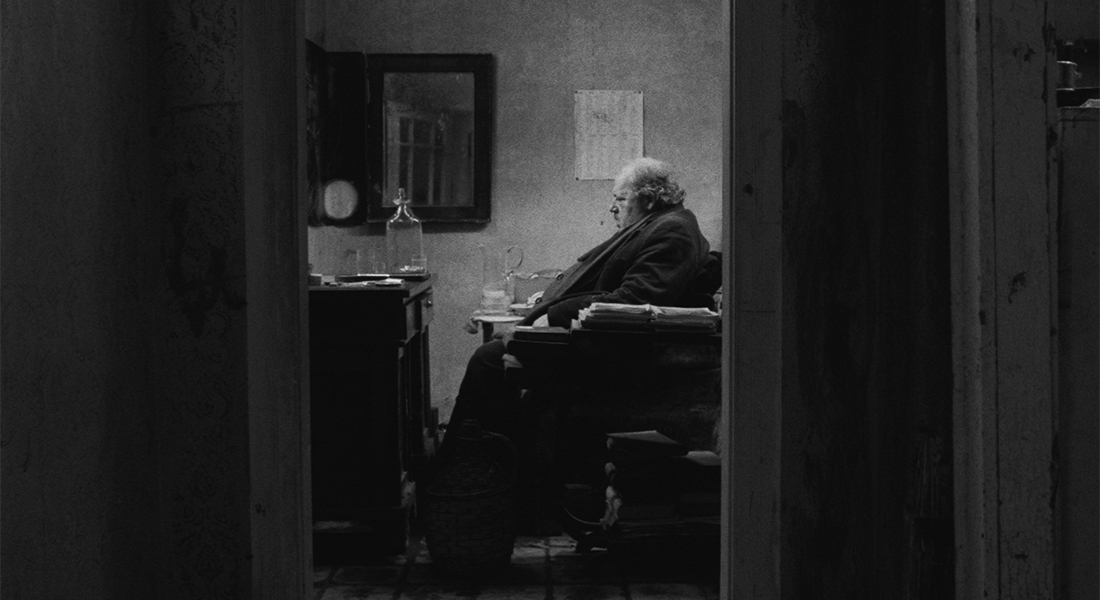

The various members are dispatched to different parts of the country, allegedly until Irimias can make the farm a reality. They all follow his directions except Futaki, who resolves to make his own way. Bureaucrats assemble Irimias’ reports (full of contempt for the members) into a professional-sounding report for their superiors, the fates of the members and Irimias himself a mystery. Finally, the doctor (who’d passed out in the woods and was taken to the hospital) returns to the commune, not realizing where his neighbors have gone. He hears the mysterious bells, and goes to investigate, eventually finding a man striking a tubular bell and crying “The Turks are coming!” The doctor returns to his house, boards himself up inside (with at least a full jug of fruit brandy), and begins to write the story we’ve just seen.

So yes, there’s more plot in the last 40% of the film than in the first 60%, but even then, we’ve got plenty of long, long takes; a slow, rotating pan shot of the sleeping commune members as a narrator details their dreams, a tracking shot towards an owl sitting on a broken rail, and the scene with the bureaucrats, done in two long takes, complete with them pausing their work to eat snacks and read the paper. I should note that the film is based on a novel by Tarr’s colleague László Krasznahorkai (which I really should read), a novel in which each chapter is a single paragraph (and most sentences are very long), a novel which is adapted practically word-for-word, accounting in part for the film’s enormous length. But Tarr had been working with long takes and slow pacing for some time before making this, so they were really a match made in Cinema Heaven.

Now, it’s much more of a toss-up as to whether you and the film itself will meld so well. And I’ll just go ahead and say it: I’m not convinced this needed to be over seven hours long. Much of the time, Tarr’s approach works, but other times, I began to feel a bit sleepy. Maybe that’s just me. Maybe it would be different in a theater. But looking back at my old review, I felt the same thing seven years ago. There are simply points were I’m not sure we’re gaining anything from looking at a virtually static image for minutes on end. Or that we needed to hear Vig’s melancholy accordion score, mostly consisting of a single repetitive theme, quite so many times and at quite such length.

That said, the film as a whole remains compelling, thought-provoking, and extremely impressive as a sheer achievement. That Tarr and cinematographer Gábor Medvigy were able to stage such scenes (or capture them), and make them play so well, is a huge testament to their skills, discipline, and patience. The images are well worth analyzing and meditating upon (which is good, because we don’t have much choice but to do so), thanks in no small part to the tremendous work of production designer Sándor Kállay; the crumbling commune, the rotting manor, Estike’s loft, the doctor’s home, the bureaucrats’ office, the tavern…all the settings are superbly realized, and if they were simply found that way, we can be glad they remained standing long enough for the scenes to be shot upon them.

There’s also some remarkable sound design, vital to creating the film’s immersive and often surreal environment; Ágnes Hranitzky’s editing (and her uncredited help in other departments) is obviously restrained but vital to the overall effect; and Vig’s score, while repetitive, is very good. In terms of craft, it’s remarkably sustained throughout its enormous length. And the script, credited to Tarr and Krasznahorkai but apparently heavily improvised by the cast, is in its way fascinating and thought-provoking, especially about the ways in which unscrupulous people with clear plans can inflict their will upon society, especially by turning the consciences of those who have them against themselves. There’s also ample symbolism to dissect, like the phantom bells, the cows at the beginning, and a herd of wandering horses later on; one of Irimias’ henchmen notes that they escaped from a slaughterhouse, and Irimias asks “Whose side are you on?” The reply: “My own.”

The acting is also quite good, though arguably more as an ensemble than in the individual performances. In particular, I didn’t find Vig quite as charismatic as we’re led to believe Irimias is, but he does a solid job as an arrogant manipulator. Performance-wise, the best turns come from Berling as the bellicose doctor and Bók as Estike, whose behavior is disturbing (after poisoning her cat, she walks around with its stiff body under her arm), but who clearly needs help that no one around her is willing to give. Székely B. is also solid as Futaki, who’s perhaps just a shade more perceptive than his neighbors, and Éva Almási Albert is effective as Mrs. Schmidt, who has flings with Futaki and Irimias (and, it’s implied, a few others); she looks a bit like Ava Gardner, and she knows she’s the best-looking woman in town. Naturally, Irimias condemns her in his report as well.

But the actors are really there to serve Tarr’s vision and style, and they so ably. I won’t say the film is an unimpeachable masterpiece, tempting as it is to say that a film so long and so demanding must be so, because otherwise, why would you sit through it? But it is a great film, a film full of greatness and worth the time to watch if you can spare it; it’s split into 12 chapters, so you can just think of it as a miniseries. (Put another way, it’s only 45 minutes longer than The Queen’s Gambit.) You’ve got to meet it halfway, and you may not feel the need to do so more than once, but I’d argue it’s worth it that once; as long and slow as it is, I found it far more compelling than many films a fraction of the length. It’s not the time, it’s how you use it.

Score: 92