Tyrone Guthrie’s film of Oedipus Rex is rich with fascination, both for myself personally and for students of film, theater, and the classics. It is, to put it very mildly, not a film for all tastes, not even entirely for mine when I first saw it many years ago (when I was in high school, I believe), but coming back to it, I can find much to value in the film itself even as I already value it for external factors.

For it is essentially a film recording of the production Guthrie staged at the Stratford Festival in Stratford, Ontario in 1954 and ‘55, and over the years my parents and I attended the Festival several times and saw many plays there—including several at the Festival Theatre, whose distinctive thrust stage was recreated in a film studio in Toronto for this film. To see that peninsula again stirs a memory or two.

What’s more, in 2005 we saw veteran actor William Hutt as Prospero (a role he had played for decades) in his final production of The Tempest. (We also saw him in the audience at another show, but left him in peace.) I mention Hutt because he plays the Chorus Leader here, and delivers an introductory speech which relates ancient Greek theater to modern religious ritual. And in doing so, he is one of the only players in the film to show his full face—but more on that shortly.

A considerable measure of interest for the more casual viewer comes from the young actor who stands behind Hutt during his introductory speech; none other than young William Shatner, not long before he went to Hollywood. You have to squint a bit, but there’s no mistaking those features—and one dedicated fan, in a long post with much information about the film and the original production, was able to identify one of his solo lines (he is a part of the chorus).

But Shatner isn’t the only science-fiction icon to appear in Oedipus. Douglas Rain, who provided the eerily soft voice of HAL 9000 in 2001, plays a Messenger—and since there’s a separate credit for Tony Van Bridge as “Man from Corinth,” Rain presumably plays the Messenger who delivers the news of Jocasta’s suicide and Oedipus’ self-blinding. I cannot say I recognized his voice, but I’m not sure HAL’s precise tones really reflected Rain’s normal mode of speech.

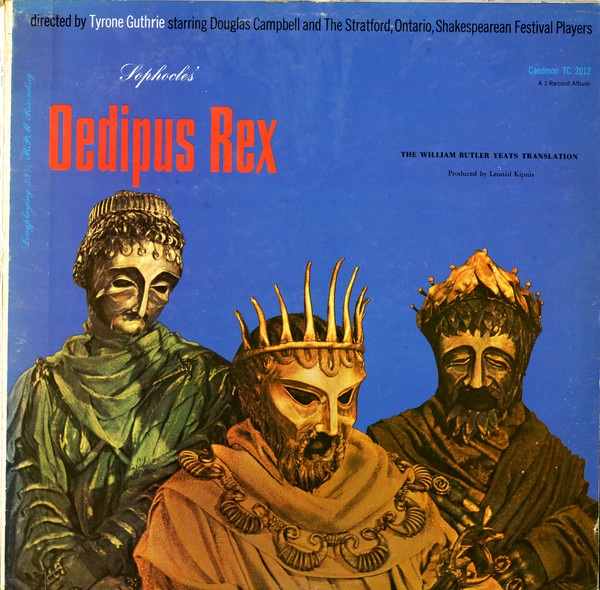

Not that many of the actors here used normal modes of speech. For this Oedipus is stylized in the extreme, being presented in the form of drama-as-ritual, with stilted movements, affected speech and choral chants—at times the actors, especially Douglas Campbell’s Oedipus, sing their lines more than speak them—and stylized masks which cover the actors’ faces.

The masks alone might be a deal-breaker for some viewers; they make the cast seem more like giant puppets than people, as only the actors’ mouths can be seen to move naturally—and given the heightened performances, not always so naturally at that. Pauline Kael’s review may sum up many viewers’ feelings:

…but the camera destroys even ordinary stage distance and brings us smack up against painted, sculpted papier-mâché. One may feel benumbed, looking at the mouth openings for a sign of life underneath.

5001 Nights at the Movies, p. 539

For my part, I appreciated the craft Tanya Moisewitsch put into the masks and costumes, and I might even argue that they help to make the affected, ritualistic style of performance more digestible than it would be with the actors’ bare faces—in much the same way I’d argue that modern-dress Shakespeare so often suffers by making his language seem more removed from our own, rather than more resonant.

The masks are tailored to each character, not just in design but in color. Oedipus wears a gold mask and a golden-brown robe; Jocasta wears a silver mask and a light blue robe; Creon wears a bronze mask and a greenish-brown robe; Tiresias wears a white mask and robe; Oedipus’ guards wear white masks and black hooded tunics; and the chorus wear what seem to be clay masks with vaguely naturalistic colorings and earth-toned robes.

Between the masks and the stylized speech, the performances are difficult to evaluate, but certainly by and large they seem to fit into Guthrie’s conception—and most of the cast had two seasons to perfect their takes on the roles. As Oedipus, Campbell occasionally goes over the top—when recounting the murder of Laius, he lets out a series of animalistic bellows which might induce an unintentional chuckle or two—but for the most part he’s effective as a figure of regal force and epic tragedy, especially in showing how Oedipus’ inner sense of dread mounts with every new revelation.

A bit less successful is Eleanor Stuart’s Jocasta; she’s okay, but something about her performance seems a bit too courtly and restrained; she seems to belong more to Victorian England than ancient Greece. (That her mask makes her look a bit like Rosie from The Jetsons doesn’t help.) Rather better is Robert Goodier’s Creon, who’s able to get a bit of sly humanity across in his confrontations with Oedipus, and is able to hint that, even if Creon didn’t collude with Tiresias to accuse Oedipus of Laius’ murder, he is not unhappy to have gained control of Thebes as the play comes to an end.

There are other solid performances, especially Tony Van Bridge as the good-natured Man from Corinth (generally called “Messenger” in the play) and Eric House as the haunted old Shepherd, but really, it’s Guthrie and Sophocles’ text as translated by Yeats that are the true stars here. This was Guthrie’s only theatrical film as a director (he also did a bit of television direction), and he reputedly received assistance from the blacklisted writer-director Abraham Polonsky; Irving Lerner, who would later direct a number of B movies as well as the film version of The Royal Hunt of the Sun, is credited with “Film Continuity.”

Whoever was calling the shots behind the camera, it’s really just a filmed play, with comparatively little use of cinematic technique to heighten the experience, and as such, the casual viewer may find this Oedipus rough going. The pace is deliberate, even poky at times (Richard C. Meyer’s editing isn’t especially distinguished), and while I find Roger Barlow’s cinematography handsome, especially in its muted colors, it can only add so much intimacy and immediacy to so stylized a presentation.

But for students of theater and mythology, it’s amply rewarding, not only for its valiant efforts in recreating ancient theatrical practice, but for presenting one of the great mythological narratives in a way that really allows you to feel the walls closing in on Oedipus with every new revelation, as every avenue by which he could escape his prophesied horrific fate is closed off. To such viewers, Oedipus comes recommended.

Score: 79

I want to finish with Tom Lehrer’s song “Oedipus Rex,” which was written to provide the film with a title song “people could hum”: